The Work Goes On

Late last week we uncovered the top of a fairly substantial mud brick wall running across the Taharqa Gate square (left), but we only had its north face. On Saturday we opened a new area to the south of this square, hoping to find the wall’s south face.

We got more than we expected. On the left you can see the line of the south side of the wall across the Taharqa Gate square. To its south (right) are 2 ash-filled ovens that were set in a layer of disturbed earth lying over part of the wall. To their south, 3 rows of baked brick with mud brick to their south cover the rest of the area. The mud brick seems to continue into our southern square, below the levels reached to date. Investigating this complex will be interesting.

Aside from the wall on its south side, so far this small limestone wall is the sole architectural feature in the square opposite the Taharqa Gate, which continues to produce lots of dirt and pottery but very little else.

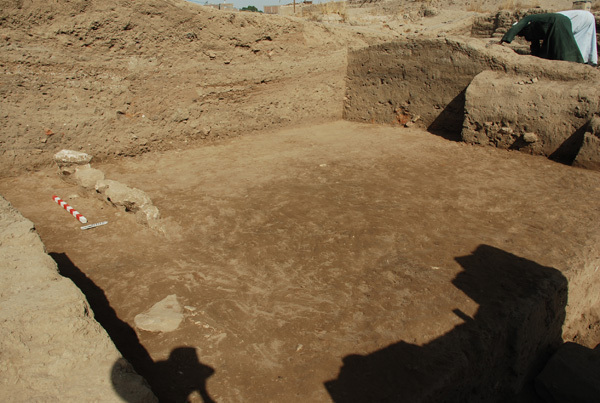

In the southern square we cleared some of the intrusive pieces of brickwork, bringing the central area down to a single level. Here you are looking east across the square, where it’s beginning to look as though there really is an alley or passage between the baked brick building on the right and the rest of the buildings.

Work on the south wing of the Taharqa Gate continues at a great rate. By Thursday 3 courses of stone were back in place, and the masons were able to move one of the more delicate blocks of the 4th course back into position.

With the removal of some of the mound of earth to the west of the Taharqa Gate, it is now possible to appreciate the gate’s full width (almost 7 meters) and to get a clear view through it to Temple A, in the northwest corner of the precinct.

We were happy to welcome Dr. Ben Harer back this week. Ben has been doing invaluable work for us the past few years drawing pottery, a task that he performs with skill, patience and good humor. When finished, the drawing he is working on will show both the exterior of the pot and the shape and thickness of its walls. Such drawings are essential to the publication of an expedition’s pottery finds.

Pottery is one of the most useful materials archaeologists dig up. It does not corrode like metal or decay like organic materials and is used for everything from food preparation and serving to transporting goods. Because it is so common, changes in style occur fairly quickly, allowing us to date various types of pottery (and the levels in which they are found) at least relative to each other. When found with coins or other datable material (e.g., inscriptions, imported wares of known date), closer dating is possible – within limits. It is rare to be able to say “this pot was made in 20 BC”; we normally speak of ranges such as “third century BC” or “late Ptolemaic to early Roman Period”, which is the range of these sherds.

This is how pottery looks when it comes out of the ground. Each basket represents a single location, which is written on the label attached to the basket. It is important to keep the baskets separate as mixing pots from different areas can lead to confusion in dating.

Before you can determine anything about the pottery, you have to be able to see it clearly, so the first stage is to wash the sherds, a job that Ahmed has been performing admirably this year (left), using a shower pan as a basin (a clever idea of the Johns Hopkins University team). Once cleaned the sherds are spread out on plastic mats to. When examining the cleaned pottery (right), we look for vessels that can be reconstructed and for “diagnostic” sherds such as rims, bases and handles that identify particular styles or types of vessel. We also look at surface treatments: has the clay been painted or covered with a thin coating of clay (called a slip)? What kind of clay is the pot made of? What has been mixed with the clay, for example to make it easier to work or able to stand a higher firing temperature?

Selected diagnostic sherds are photographed, which we are able to do this year right next to the pottery mats. This set-up allows enough soft side lighting to bring up details of the pottery (right) without casting harsh and distracting shadows. Photographs are used in conjunction with the pottery drawings in further study of the pots.

Thanks to Dr. Mansour Boreik, General Director of Antiquities for Southern Upper Egypt, Mary and I were lucky enough this week to be able to visit the mosque of Abu el-Haggag, built on the ruins of the Luxor Temple. The minaret on the left dates probably to the Fatimid Period (10th-12th century AD), but the rest of the mosque was rebuilt in the 19th century.

Restorations made necessary by a disastrous fire a few years ago revealed that the mosque’s walls actually incorporate Ramesside columns and architraves. Below the 10th-12th century AD minaret is a 13th century BC Ramesside architrave that includes a rare relief of an elephant. This photograph is illustrated courtesy of Dr. Mansour Boreik, who will be publishing the results of the work at the mosque in a forthcoming issue of Memnonia.

Richard Fazzini joined the museum as Assistant Curator of Egyptian Art in 1969 and served as the Chairman of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art from 1983 until his retirement in June 2006. He is now Curator Emeritus of Egyptian Art, but continues to direct the Brooklyn Museum’s archaeological expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak, a project he initiated in 1976. Richard was responsible for numerous gallery installations and special exhibitions during his 37 years at the museum. An Egyptologist specialized in art history and religious iconography, he has also developed an abiding interest in the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. Well-published, he has lectured widely in the U.S. and abroad, and served as President of the American Research Center in Egypt, America’s foremost professional organization for Egyptologists.