Elephant Mask on View

Once permanent installations are set into place, the opportunities for placing previously unseen works on view are rather rare—even with a collection as deep (with over 6000 objects) and well-regarded as Brooklyn’s collection of African art (ranked among the most important holdings of art from the African continent in North America). The chief opportunities come from outward loans of objects on display in the permanent galleries, allowing an equally intriguing work from storage a “guest spot” in the open casework, or through textile rotations. (Look for more on the latter in another posting.) Thus, it was with considerable pleasure that I, along with our crack Art Handling, Conservation and Design teams, was able recently to return our Kuosi Society Elephant Mask, by an unknown artist working in the Bamileke style, to view from an extended hiatus in storage.

The circumstances for the Elephant Mask’s return were a bit unusual. As you may have noticed, it currently has pride of place in our shop, gracing the cover of the newly published catalog of the African collection, African Art: A Century at the Brooklyn Museum.

The mask was one among a series of candidate objects, of the roughly 130 in the book, for the cover slot on the catalog (more on this process another day, as well). Once it was selected, our Chief Curator and I met and decided that it needed to be returned to view in the permanent galleries.

The Elephant Mask had last been on view in 2001, when the current version of the “Arts of the Africa” galleries was last completely reinstalled. After a brief sojourn on the 1st floor, it was returned to storage the following year, out of conservation concerns (the cloth background, from which it is primarily constructed, is best preserved with limited long-time light exposure). Unfortunately, the casework and mount in which it was displayed were not retained.

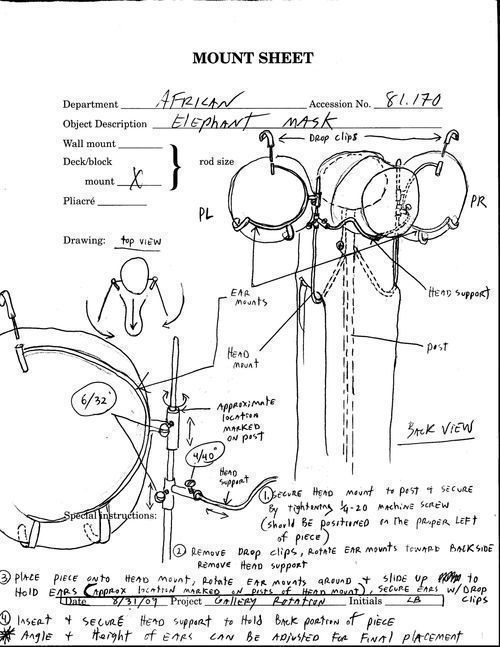

While a new case was being constructed, our Conservation team set about re-examining the work, first determining if it was stable enough for display—and, if so, for how long. Once convinced that it could be returned, our mount-maker began the task of studying the construction of the mask, in order to best design a metal mount that would both bear the weight of the entire composition and, in particular, support the large, round projecting ears, which are only loosely sewn on to the edge of the mask’s face.

The result was cleverly simple—a post that runs from the bottom of the case (largely obscured by the trunk) into a round, foam support behind the face, with two half-circles extending from the central core, running along the edge of the face and the back and bottom of the ears.

(When you examine the object closely next time in the galleries, note how the mount was painted with specks of color, to mimic the beaded patterns on which it is overlaid.)

Consultation with our Chief Designer determined that the mask could be inserted into the existing installations with minimal disruption. A late 19th century funerary headdress, or tugunga, in the neighboring Bamum or Tikar styles was re-oriented in the gallery, from the current location of the Elephant Mask onto an axis in direct line of sight with the (former) Hall of the Americas.

After a few, small paint touch-ups on the walls, the Elephant Mask was ready for its return last month.

The mask itself is among the boldest and most colorful examples of Bamileke beadwork that I know – a genre that ranges from certain types of clothing and items of personal adornment, to the decoration of large, ceremonial or political objects, like stools. Moreover, the mask remains in stunningly good condition (most such masks would have been discarded – or sold – only after they had become worn, no longer suitable for continued use). The artist has, very cannily, used a combination of complimentary shades of blue beads, against an indigo-blue cloth background, in contrast with a smaller number of red, white and ochre beads to add visual interest to the radiating circular and wedge motifs covering most of the surface. The mask, as a persona of political enforcement within the Kuosi Society, was used by the Bamileke fon, or king, in periodic displays reinforcing his own authority. (For the full gallery label, visit the object in our online collections). Better still, come examine it in person, and re-discover the depth and variety of Brooklyn’s world-class African collection.

Kevin D. Dumouchelle joined the Brooklyn Museum in 2007. He was promoted to Associate Curator for the Arts of Africa and the Pacific Islands in 2012, having served as Assistant Curator since 2008. In 2011 he conceived and curated African Innovations, the Museum’s first chronological and contextual installation of its African collection. He has also curated a number of exhibitions, and contributed to the writing and editing of a major catalogue of works in the African collection, African Art: A Century at the Brooklyn Museum, published by the Brooklyn Museum in association with DelMonico Books • Prestel in fall 2009. Dumouchelle has published on a range of topics, from architecture and canonical African sculpture to contemporary photography, and he has received numerous fellowships and awards. Dumouchelle earned an M.A. and M.Phil. in Art History and Archaeology from Columbia University, where he taught art history and is completing his Ph.D. He has pursued research in Morocco, Mali, and Ghana, and is the recipient of a first-class Master’s degree in history from Oxford University and a B.S. in Foreign Service from Georgetown University.