Take a seat…

Starting on December 2nd, that’s exactly what you’ll be able to do in the Museum’s Fourth Floor Schenck Gallery—in a handcrafted replica of our 17th-century, American, Wainscot Chair. The detailed carving, turning and mortise-and-tenon joinery of the original chair were masterfully replicated by Peter Follansbee, a joiner specializing in 17th-century reproduction furniture for over 20 years.

Left: American. Wainscot Chair, second half 17th century. Painted oak, 48 1/8 x 26 3/4 x 23 1/2 in. (122.2 x 67.9 x 59.7 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Memorial Fund, 51.158. Right: Replica chair created for the Brooklyn Museum by Peter Follansbee, joiner.

Mr. Follansbee visited the Museum in March of this year to examine the chair and take measurements. His goal: accurately recreate the work of 17th-century craftsmen, whose techniques can be observed on the chair in details like original handmade pins and joiner’s marks on the legs.

Detail of original hand carved pins and joiner’s marks from the original.

Details of the replica chair during construction at Peter Follansbee’s workshop. Images courtesy of Peter Follansbee.

While Mr. Follansbee started replicating the chair, conservators began an examination to determine the original paint scheme. Although many of these chairs are now painted black or other dark colors, it is unlikely that this was done by the original craftsmen. We wanted the completed replica chair to accurately reflect what the original would have looked like before centuries of use.

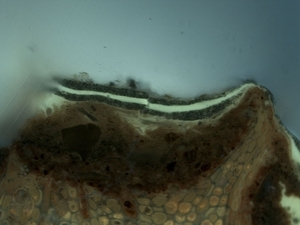

Several paint samples were taken from various locations on the chair and made into cross-sections. Cross-sections are an important tool for conservators, allowing us to view the different paint layers and coatings and the order in which they were applied to the surface. Paint samples are mounted in resin, polished and examined with a polarized light microscope.

The cross-sections revealed that the chair had received several applications of paint and varnish. The earliest paint layers appeared to be a bright red and a darker brown followed by multiple applications of the black paint. Red paint was also observed underneath the black paint on the surface of the chair. Natural resin varnishes, which appear green under ultraviolet light illumination, are also visible as later applications in the cross-sections.

Left: Detail of paint cross-section in visible light from the back of the chair showing the lowest red and brown paint layers, followed by multiple layers of varnish and black paint. Right: Detail of paint cross -section in ultraviolet light from the back of the chair showing the lowest red and brown paint layers, followed by multiple layers of varnish (which appear bright white/green) and black paint.

According to Chief Curator, Kevin Stayton, and Curator of Decorative Arts, Barry Harwood, these chairs could have been painted or left unpainted after manufacture. In addition, painted surfaces may have been applied shortly after construction but not by the craftsmen who built them and reflect the history and use of the chair. Although the earliest application of paint is red, it could not be determined when this layer was applied.

Following a discussion between conservators, curators and Mr. Follansbee, the replica chair was not painted. We hope that the contrast between the natural and wonderfully hand carved oak of the replica and the patinated original will highlight the intricacy of the handcrafted details, create a closer representation of the chair’s original appearance and accentuate the historic changes that objects such as the Wainscot chair can undergo before entering the Museum’s collection. The replica chair has been coated with oil & turpentine to protect the wood so that it can be appreciated by Museum visitors.

Kerith Koss is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Objects Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum. She received her Master's Degree in Art History and Conservation from the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Before joining the Brooklyn Museum in 2008, she was a Smithsonian Post-Graduate Fellow at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Over the course of her conservation training, she has completed internships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Field Museum in Chicago and the Shelburne Museum in Vermont and has assisted in hurricane recovery efforts at several local museums on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi.