A new project and a few surprises

To the ancient Egyptians, magic (heqa in ancient Egyptian) was a potent force that could be used by deities and humans to influence the mortal world. These blocks come from a small (less than 2 meters square) 26th Dynasty magical healing chapel that once stood in the precinct. Visitors (or priests) would recite the spells written on its walls to cure illness. The building was eventually dismantled and its blocks re-used in a late Ptolemaic or early Roman Period building. Richard decided this year to re-erect the chapel, and work began this week.

Since we don’t know where the chapel originally stood, we are rebuilding it in front of the east wing of the Mut Temple’s 1st pylon, with the permission of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. To create a firm foundation we put down a bed of sand with a layer of gravel above it on which we poured a base of cement reinforced with rebar (left). Next came a water barrier of plastic sheeting and bitumen cloth before the final sandstone platform was built (right). Khaled is supervising the work, which is being carried out again this year by mason Mohamed Gharib (bending over) and a small crew.

Putting the bottom blocks of the right and rear walls in position on the new platform was relatively simple, but for the next course of the right wall we needed a tripod and winch (“siba” in Arabic). On the right, Jaap and Khaled make sure that the block is properly positioned before it is lowered the final few centimeters. It is painstaking work.

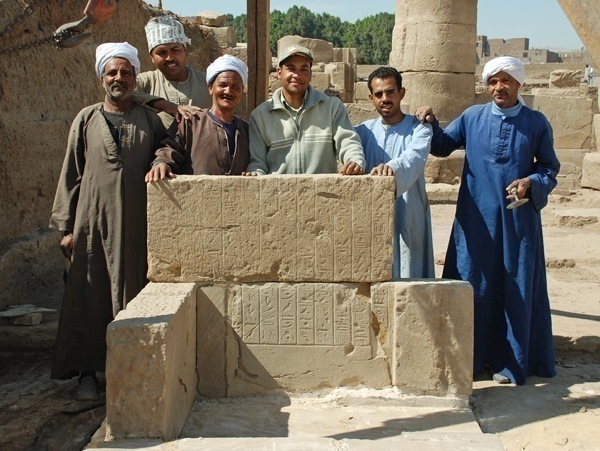

By the end of the week the first 3 blocks are in place, with the columns of text on the right wall perfectly aligned; Khaled and his team are proud of their work.

Ayman continues to work on the expanded square north of the Taharqa Gate. On Tuesday he called us over to see something odd: an apparently empty jar (only the rim is visible) set into the ground. Usually buried vessels are full of dirt. When he began to clear around the jar neck, he found a couple of coins, visible behind his trowel (right).

Fortunately conservator Anna Serotta joined us this week. Anna is a Mellon Conservation Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum and was a conservation intern in Brooklyn last year. Of most importance to us right now, her work at the Turkish site of Aphrodiasis has given her lots experience with ancient coins, which she immediately put to use.

Anna brushed loose dirt off the coins so they could be photographed (left). There turned out to be not 2 but 5 coins in this group (right).

Just before the breakfast break Anna was able to take out the coins and put them in a muffin pan (left), which we have found very useful for transporting small objects (archaeology requires the ability to adapt). Imagine our surprise when we got back from breakfast and found yet more coins against the side of the pot (right). We ended up with a total of 13.

On the left, the coins as they came out of the ground. There really are 13: the one on the lower right is actually 2 stuck together. The surface encrustations are very hard, but by Thursday Anna had managed to remove enough from 4 of the coins to give us some idea of their original appearance (right). We sent these pictures to Dr. Penelope Weadock Slough, retired Curator of Ancient Art at the Detroit Institute of Art and an expert in ancient coins. According to her, the obverse of 2 coins shows Zeus wearing the ram’s horn of Amun, while the reverse of 3 has a pair of eagles looking left. She has tentatively dated the coins to Ptolemy IX Soter II who ruled twice: 116-107 BC and 88-80 BC (after the death of Ptolemy X, his successor who left no heir). Thank you, Penny.

Yet another surprise: from what we could see we expected the coin pot to be a fairly small, rounded vessel. Instead we got a tall, elegant jar with a flat bottom (right) that had been set upright on the ground. Its mouth had been covered by a small finely-made bowl that kept it from filling entirely with dirt; the bowl is in several pieces and Anna is working to repair it.

Ayman’s area keeps getting more interesting. In the west half the Dynasty 25 enclosure wall now runs all the way to the south face of the present enclosure wall, although it is cut by pitting. To the east there seemed nothing left of the ancient wall, but we decided to dig a little deeper. Our persistence (and Ayman’s) was rewarded by the discovery not only of more brick (center of the photo) but of a layer of sand at the south end of the area. This may be the sand foundation bed of the wall.

When we removed the layer of broken stone and pottery in the corridor south of the Taharqa Gate, we found a layer of stone rubble that ran up to the Taharqa Gate wall. It is clearly the base on which the northern part of the corridor’s west wall (right) and the brick against it were built.

At the south end, however, the wall continues to a greater depth, as you can see here, suggesting it was partially built to fit the contours of the land. A narrow row of baked brick runs across the south end of the corridor, with mud brick to its south, although somewhat cut up. The heap of baked brick probably fell from the well above that we excavated in an earlier season.

After 2 weeks of digging through more than 1.5 m of dump, Abdel Aziz finally has a new feature in his square on the high ground west of the Taharqa Gate: a row of baked brick and stone, including a piece of fleece from a large granite ram sphinx. It doesn’t yet connect to anything but it’s better than nothing.

Before we can remove the upper courses of brick in Abdullah’s square south of Abdel Aziz Bill needs to map them (left). In the meantime, Abdullah and his team have moved south to the area just west of the complex of brick found in 2009. To no one’s surprise he has found more brick (right).

Mary McKercher holds a BA in Ancient Near Eastern Studies (specializing in Egypt) from the University of Toronto and is also a trained archaeologist. In 1979 she joined the Brooklyn Museum’s expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak as photographer and archaeologist, roles she continues to fill. She has contributed to the Mut Expedition’s “Dig Diary” since it began in 2005, and put together the photographs for the 8 Mut Expedition photo sets on the museum’s Flickr site. With her husband, Richard Fazzini, she has also researched and written about the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, commonly known as Egyptomania.