Papyrus: Secret of the Egyptians

Although the making of papyrus as a writing support is almost 5,000 years old, not a single written description by the Egyptians exist to explain their process.

Pictorial displays in tomb murals and carvings never reveal the process of sheet formation, though often depict the papyrus plant. Only one document by Pliny the Elder, Natural History, XIII, written in the 1st c. A.D. attempts to describe the process of papyrus making. Unfortunately, this description is ambiguous and so lacking in details it has led many to believe Pliny never actually saw the process first hand. By the 10th c. AD papyrus making becomes extinct and the secret of its fabrication appeared to be lost.

Papyrus is made from the sedge plant, Cyperus papyrus which grows in shallow water and was so abundant in ancient Egypt it was the source not only for the manufacture of flexible writing supports but for many everyday items such as shoes, coverings, boats, and food. Ironically, by the 20th century this plant no longer existed in Egypt though it has since been imported and cultivated. We don’t know whether the ancient Egyptians used wild or cultivated Cyperus papyrus plants of which there are many sub-species. Any one of these sub-species could have affected the quality and finish of a papyrus sheet. Nor do we know the tools and equipment which might have been used by the workshops producing the papyrus sheets. Thanks in large part to scientific analysis, conservation examinations and modern attempts at papyrus making by researchers, curators and conservators we have unlocked some of the basic secrets ancient Egyptian papyrus making.

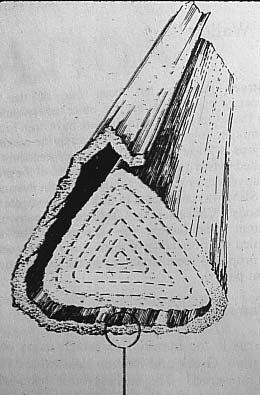

The Egyptians cut the triangular green stalk close to the waterline and eliminated the flowering head.

When the outer green rind is removed a soft white triangular pith is exposed (above). The pith was cut into strips either along the triangular faces of the stalk or straight through the triangle. At times the pith was unwrapped down to its core (below).

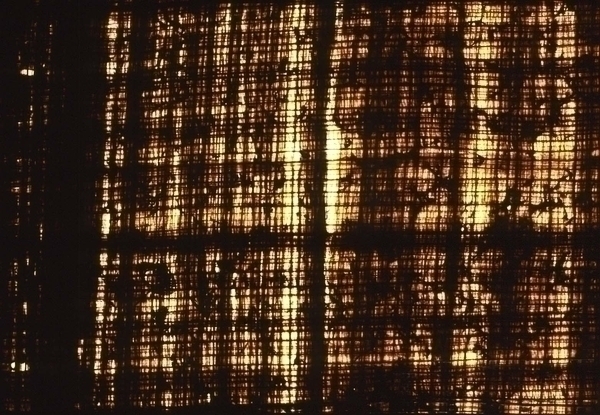

Scanning electron microscopy (extremely high magnification) can distinguish between the strip or peel method and indicates that both were used in antiquity. The strips or peeled papyrus were soaked in water to swell the fibers and cells. While wet the white pith yellows and darkens. Individual strips were laid upon a smooth surface, side by side and slightly overlapping. Then a second set of strips were laid onto the first, perpendicular to it. The two layered sheet is then hammered, rolled or beaten flat and then pressed while still moist. If the pith was peeled, two layers with fibers perpendicular to each other were pressed together.

The Egyptians always made papyrus sheets with this two layered laminate structure easily identified in transmitted light by a characteristic grid pattern. The criss-cross dark lines are the fiber bundles which run parallel to the stalk and which transported water and nutrients. Because of the perpendicular laminate structure, the fibers run horizontally on one side and vertically on the opposite side. The fibers give the sheet its strength. The lighter material in between the dark lines are the plant (parenchyma) cells also called the ground tissue they fill and give body to the framework.

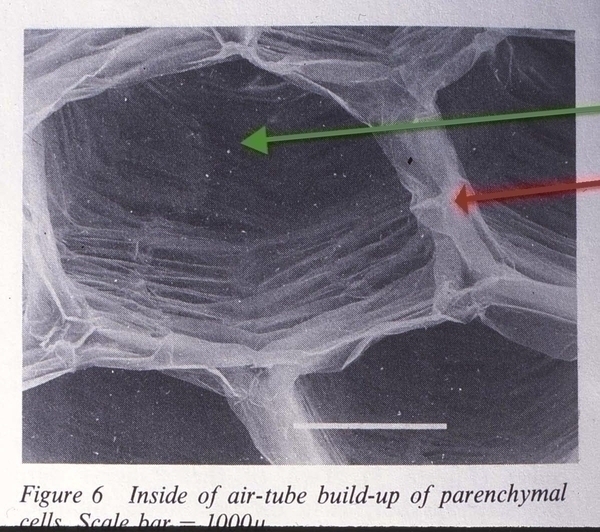

There is still debate over whether the Egyptians added a glueing agent to adhere the two perpendicular layers of papyrus together. It is possible they did so in certain periods and not in others. Analysis and a variety of modern experiments repeatedly show that papyrus could have been made without any extraneous adhesive. The explanation for adhesion of the two layers to form a sheet is a physical and mechanical one. The parenchyma cells or ground tissue are stacked in a honeycomb like network running the length of the stem. These cells (red arrow) surround large hollow air ducts (green arrow) and look like this at very high magnification.

When pressure is applied to overlapping strips of papyrus and to the perpendicular layers (press, rolling, hammering etc) the air ducts collapse causing the plant cells to merge into each other filling the hollow spaces and forming a dove-tail like join. Upon drying the merged cells lock causing complete and long term adherence between the layers and creating a sheet of papyrus.

—-

This post is part of a series by Conservators and Curators on papyrus and in particular the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sebekmose, a 24 foot long papyrus in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. This unique papyrus currently in 8 large sections has never been exhibited due to condition. Thanks to a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, the entire papyrus is now undergoing conservation treatment. The conservation work is expected to last until fall 2011 when all 8 sections will be exhibited together for the first time in the Mummy Chamber. As each section is conserved, it will join those already on exhibition until eventually the public will see the Book of the Dead in its entirety.

Toni Owen is Senior Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum. She joined the staff in 1986 to help plan the Museum’s paper conservation laboratory. Toni received her Master’s Degree and Certificate of Advanced Study in Conservation from the State University of New York, Cooperstown, New York. Prior to the Brooklyn Museum Toni was a Mellon Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and from 1977 until 1985 she was head of Paper Conservation at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution.