IR and UV Examination of Egyptian Papyrus

Following Rachel’s previous discussion on pigments and inks used in our Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose, I will begin here our discussion of the different examination and analytical techniques we employ in conservation and the ones used on this object in particular. I will start with two imaging techniques: infrared reflectography and ultraviolet fluorescence photography.

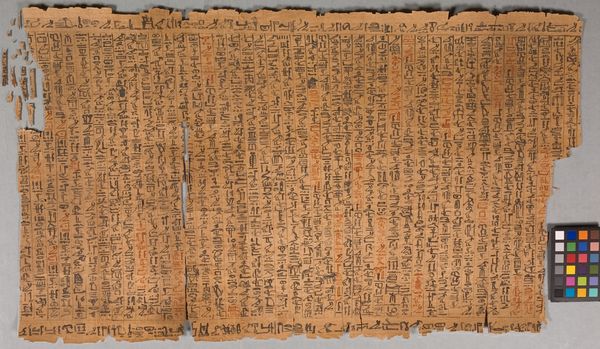

We typically use traditional photography to record images of artifacts in the visible light spectrum; this way we record on a digital file that which the human eye can see (fig.1). However, this technique can provide only a limited amount of information, since the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum is a very small portion (400-700nm) of the entire spectrum. By eliminating the visible light using barrier filters, we are able to record images that the unaided human eye could not detect. Generally, we record images in the near infrared (700 to 900 nm) as well as the ultraviolet ranges (200- 400nm).

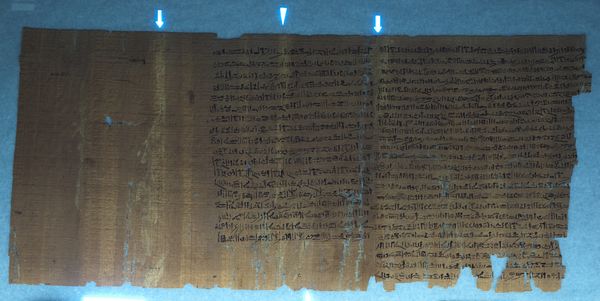

Fig.1 Fragment from the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1479-1400 B.C.E. Ink and pigment on papyrus. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.1777E. Illuminated with visible light.

Infrared reflectography is often used in conservation to ‘see through’ paint layers that are impenetrable to the human eye and thus reveal underdrawings, underpaint, artist’s changes or pentimenti. Carbon black, one of the pigments used for chants and spells in our papyrus, is very absorbent of infrared radiation, which can help with deciphering inscriptions that have faded or been partly erased or even almost completely obliterated (e.g. charred documents).

It is now possible to capture high quality infrared images with a digital camera. Infrared radiation generated by a light source such as a tungsten bulb falls on the subject, and then reflects off it on to the camera. With the help of an IR filter placed over the lens to block the visible light from passing through, a record of how the subject reflects the infrared radiation is created.

In our IR reflected photograph (fig. 2), the carbon black text on the papyrus fragment, heavily absorbs the infrared radiation and thus appears even more intense, while the iron oxide red pigment appears almost transparent as iron absorbs poorly in the infrared region.

Fig.2 Fragment from the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker Amun, Sobekmose. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, ca. 1479-1400 B.C.E. Ink and pigment on papyrus. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.1777E. Illuminated with infrared light.

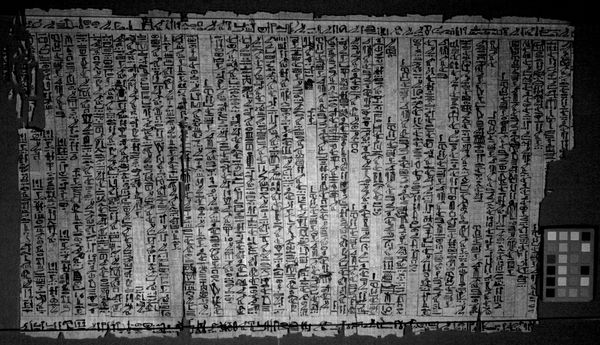

Certain compounds can easily be detected under UV light, because they absorb this invisible (UV) energy and then re-emit it in visible light. Most UV examination lights, or black lights, emit wavelengths in the 350-360nm region (UVA). A UV filter is placed over the camera lens to block the visible light and exposing the ultraviolet sensitive sensor. This imaging methodology is called ultraviolet fluorescence (UVF). Natural resin varnishes, certain adhesives and pigments have their own characteristic fluorescence under UV light. UV radiation examination also provides information on materials which absorb and do not fluoresce, for example retouchings appear as dark patches on the varnish surface.

In our papyrus, the pigments did not exhibit characteristic fluorescence colors. They generally absorbed the UV radiation because they are metallic based and thus appeared dark. (fig. 3)

Fig. 3 Fragment from the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker Amun, Sobekmose; recto. Illuminated with ultraviolet light. The yellow ochre, red iron oxide and malachite (marked with corresponding colors) strongly absorb the UV light.

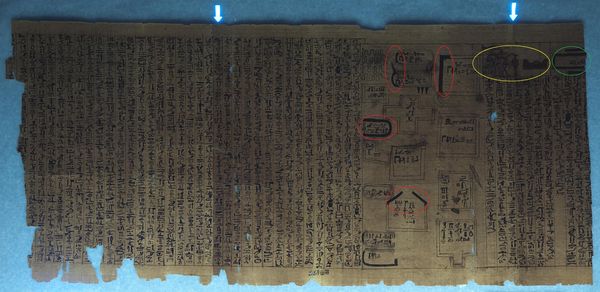

One of the most important questions we wanted to answer was whether an adhesive was used along the overlap of the papyrus sheets to form this papyrus roll. Viewing the verso of the papyrus under ultraviolet radiation, we noted an intense yellow- white fluorescence along the joins of the roll as well as in the location of old papyrus mends. This UVF suggests the presence of an adhesive, possibly a starch based one, used to join the sheets and make repairs (fig. 4). This was confirmed with a chemical spot test (Iodide Potassium Iodine) on a few samples of the fluorescing material. The strongly fluorescing areas were lightly swabbed with damp cotton, which turned black on the application of a small drop of 1% iodine solution.

Fig.4 Fragment from the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker Amun, Sobekmose; verso. Illuminated with ultraviolet light. The arrows indicate the joins (kolleses) whereas the triangle marks the area of old papyrus repairs performed after the scroll's manufacture and before the writing of the text.

—-

This post is part of a series by Conservators and Curators on papyrus and in particular the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sebekmose, a 24 foot long papyrus in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. This unique papyrus currently in 8 large sections has never been exhibited due to condition. Thanks to a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, the entire papyrus is now undergoing conservation treatment. The conservation work is expected to last until fall 2011 when all 8 sections will be exhibited together for the first time in the Mummy Chamber. As each section is conserved, it will join those already on exhibition until eventually the public will see the Book of the Dead in its entirety.

Pavlos is project conservator of paper at the Brooklyn Museum. He joined the conservation department in 2008 to assist with the conservation of the Egyptian Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose, a unique papyrus artifact in the long - term installation The Mummy Chamber.