Season 25 is underway

We began what will be mainly a study season on January 11 with the traditional cutting of the camel thorn. Fortunately there isn’t much as we had arranged with the SCA and Reis Farouk to have our part of the site cleared in October. It took the whole day to clear this area and more camel thorn remains elsewhere.

Our inspector this year is Amer Hassan Hanafy, shown here with Reis Farouk. We first met Amer about 10 years ago when he was part of a team of SCA inspectors who carried out excavations in the Mut Precinct and worked on the sphinx avenue north of the Mut Precinct. It’s good to see him again and to have Reis Farouk with us once more.

Our Qufti this season are Abdel Aziz Sharid (right) and Mamdouh Kamil, both of whom have worked for us for many years. To their left is the south wall of the approach to the Taharqa Gate. The wall’s east end is obscured by the remains of one of last year’s baulks. We want to remove the baulk this season to find out what is left of the wall below it.

Here’s the area at the end of work on Thursday (left), with most of the baulk stub gone. As you can see in the photo on the left, the east end of this section was destroyed, by the pitting that characterized this whole area. Only parts of the 3 northern rows of the wall remain at a lower level (right) and even they are disturbed. The big hole in the wall is part of an animal den that tunneled through the area.

At the end of 2010 we thought that we might have found the point at which the mud brick running north-south along the full length of the west side of the excavation area made a corner with the east-wall at the south end of the excavation. As is evident in this photo taken then, the brick was very friable, its excavation requiring more time than we had left. Clearing up this question is one of this season’s goals.

We extended the excavation further to the south and by mid-morning on Thursday (our 2nd actual day of digging) knew that last year’s theory was wrong: not only does the long wall keep on going, but it gets wider. The meter stick is on the newly-found brick of the long wall, and the north arrow sits on another wall that meets the long wall’s west face. We do have a corner, but it is an inner corner where the east face of the long wall meets the south face of the large east-west wall mentioned above.

The newly-exposed brick was cut by a pit whose edge is visible on the left. Below it the brick continues. In the newly-revealed angle of the walls we have come upon an ashy layer with a considerable amount of pottery, including a Hellenistic black-glazed bowl that is clearly visible in this photograph. This area is proving more interesting (and complicated – what a surprise!) than expected.

Our first small find of the season: the head and shoulders of a terracotta female figure wearing an elaborate (if crudely executed) wig. It came from the loose earth over the long brick wall on Wednesday. We have found several similar figures over the years, all broken in roughly the same place.

We had a number of welcome visitors early in the week. Ahmed Araby (to Richard’s left in the photo on the left) dropped by to say hello. He was our inspector in 2001 and is responsible for much of the work on the sphinx avenues outside the precinct. Later in the morning, François Larché, former Director of the Centre Franco-Egyptien d’Etude des Temples de Karnak; and Nicholas Grimal, former Director of the IFAO came by as well. I took this picture from the roof of our equipment storeroom where I was photographing the sphinx avenues.

The work on the sphinx avenues built by Nectanebo II is of considerable interest to us. They formed part of a complex of processional ways linking the Luxor Temple, the Mut Precinct and the Amun Precinct. The SCA archaeologists discovered recently that the avenue running north from the Luxor Temple and along the west side of the Mut Precinct (left) forms a T-junction with the avenue that runs along the north side of our site. This latter avenue continues west toward the Nile instead of simply ending at a corner.

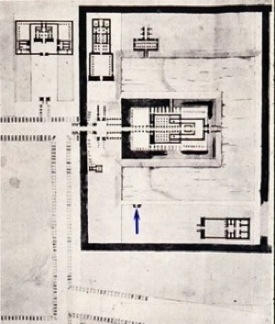

What is fascinating is that a little-known plan by French explorer Nestor L’Hôte, drawn in the late 1830s and called a “reconstruction drawing” (right), seems to show just this combination of sphinx avenues, including the New Kingdom avenue from Amun to Mut (left) and the avenue leading to a Ptolemaic gateway in the Amun Precinct’s south wall (lower left). While his proportions are not exact (the Mut Precinct is too square and too short), the major monuments are all there and in roughly the correct relationship to one another. By the late 1800s, the Nectanebo II sphinx avenues and other building remains were no longer visible, including the small gateway in the Mut Precinct (arrow). We re-discovered it in 1983, precisely where L’Hôte said it should be and it proved to have been built by Tuthmosis III and Hatshepsut.

Mary McKercher holds a BA in Ancient Near Eastern Studies (specializing in Egypt) from the University of Toronto and is also a trained archaeologist. In 1979 she joined the Brooklyn Museum’s expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak as photographer and archaeologist, roles she continues to fill. She has contributed to the Mut Expedition’s “Dig Diary” since it began in 2005, and put together the photographs for the 8 Mut Expedition photo sets on the museum’s Flickr site. With her husband, Richard Fazzini, she has also researched and written about the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, commonly known as Egyptomania.