Looking for Adhesives and Identifying Binders in the Book of the Dead Using FTIR

Another scientific analytical technique commonly used in art conservation is called Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy, or FTIR. The Brooklyn Museum’s Paper Conservation Lab employed this technique to continue analysis of the Brooklyn Museum’s Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose papyrus scroll.

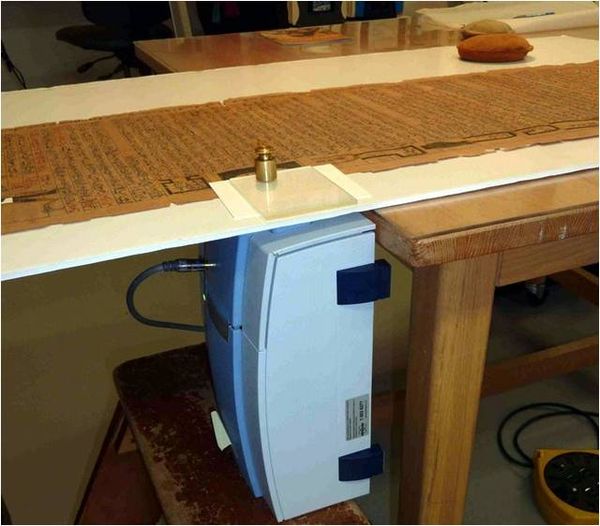

As with the XRF analysis, we were able to perform FTIR using portable equipment belonging to Pratt Institute. Eleonora del Federico, Associate Professor of Chemistry in the Math and Sciences Department at Pratt Institute brought her portable FTIR device to our paper conservation lab.

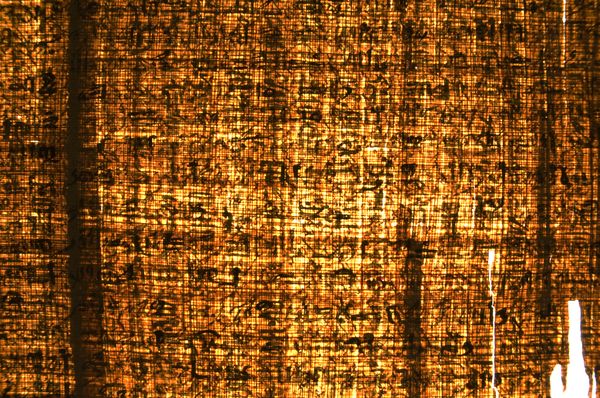

We decided to use FTIR for two reasons. One is we want to know if the ancient Egyptians used an adhesive to attach separate sheets of papyrus to form a long continuous scroll. We can see the joins where one sheet was attached to the next but it is unknown whether an adhesive was used to hold them together. Note the dark vertical line towards the far left of this image of papyrus in transmitted light; this is where two sheets of papyrus have been joined together.

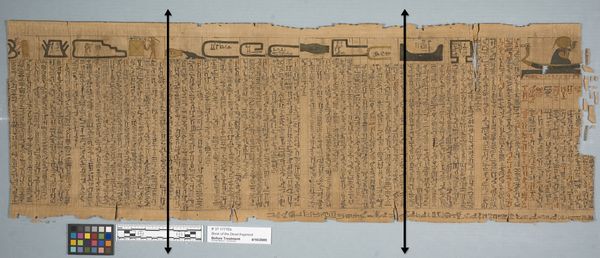

Two joins exist on this fragment, one towards the right side and one towards the left side of the piece. Samples were analyzed on areas of joins and non-joins in order to make a comparison.

Secondly, we want to try and identify the binder in the pigments used to write on and illustrate the Book of the Dead.

FTIR uses infrared radiation to observe the vibrational changes in chemical bonds in order to identify certain functional groups. From this information, certain types of materials can be identified as protein-based, cellulose-based, etc. and this can help us to determine if an adhesive is present.

The FTIR device scans a tiny area over and over again to capture the vibrational changes. Here you can see the FTIR scanner placed under the papyrus. The infrared rays are directed upwards to scan the area to be analyzed. For this analysis, each scan lasted around 5 hours, amounting to over 20,000 scans for each area.

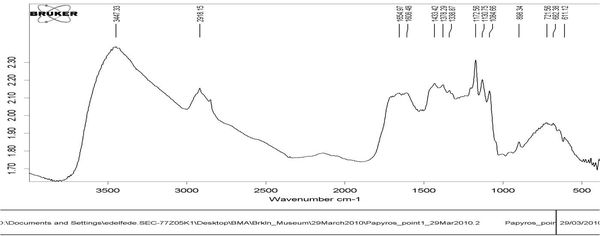

Combined, the information from these scans provide data which is viewed in the form of spectra, with many bands that represent chemical bonding between two particular atoms or a group of atoms in a molecule. The spectrum will be compared to a set of known reference materials for identification and interpretation.

We think it is possible that the ancient Egyptians used an adhesive to join the individual sheets to form a roll. If they did, it is likely that they used a protein-based adhesive such as animal glue, or a starch-based adhesive such as wheat starch paste. It is also possible that no adhesive was used, and that moisture was used in the same way that it was used to join the strips to form a sheet (see previous blog entries on making papyrus). In the latter case, moisture would be used along with extreme pressure to form a physical bond to join the sheets. We also think that the binders used with the pigments on this scroll could likely be gum arabic or animal glue. We are still awaiting results for our analysis.

—-

This post is part of a series by Conservators and Curators on papyrus and in particular the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sebekmose, a 24 foot long papyrus in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. This unique papyrus currently in 8 large sections has never been exhibited due to condition. Thanks to a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, the entire papyrus is now undergoing conservation treatment. The conservation work is expected to last until fall 2011 when all 8 sections will be exhibited together for the first time in the Mummy Chamber. As each section is conserved, it will join those already on exhibition until eventually the public will see the Book of the Dead in its entirety.

Caitlin Jenkins is currently the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Paper Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum. She received her M.A. in Art Conservation from Buffalo State College in NY and before coming to the museum she held positions and completed internships in a variety of other conservation labs at institutions including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, MA, the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, NC and the Wilson Library, also in Chapel Hill. She received B.A.s in Art History and in Historic Preservation from Mary Washington College.