The Original Avatars: An Introduction to Vishnu’s Earthly Manifestations

The Vishnu exhibition that’s on view here right now includes a large section on the god’s avatars. The show introduces the idea of the avatar as it originated in Hinduism more than two thousand years ago. Going through this part of the show, people will encounter divine, heroic figures—some of them animals—and they will learn the many stories of how Vishnu took these forms in order to save humankind over and over again.

My favorite avatar, the boar: Varaha Rescuing the Earth, Page from an illustrated Dashavatara series; India (Punjab Hills, Bilaspur), circa 1730–40. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 10 1/2 x 8 1/8 in. (26.7 x 20.6 cm) Brooklyn Museum Collection, by exchange, 41.1026

Fifteen years ago, non-Hindus had only the vaguest idea of what an avatar is. Now most can tell you that it’s an alternate form, a new body or persona that’s assumed for special purposes, such as playing a game, or joining an on-line conversation, or infiltrating a nature-loving alien culture. But the differences between the original, Hindu use of the term and the new use are pretty important.

Vishnu’s scariest avatar, the man-lion: Yoga-Narasimha; Southern India (Tamil Nadu), 12th century. Bronze, 18 3/4 x 13 x 9 1/2 in. (47.6 x 33 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Samuel Eilenberg Collection, New York, Bequest of Samuel Eilenberg, 1998 (2000.284.4). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

First of all, in Hindu tradition, mere mortals don’t have avatars. The ability to assume new bodies is purely divine, and for the most part it is reserved for Vishnu, who is one of the most powerful deities in the Hindu pantheon—some would say the most powerful. The fact that alternate digital personae are now called avatars actually makes a lot of devout Hindus quite uncomfortable or angry, because the comparison belittles the divine avatars of their religion. In the Hindu context, avatars aren’t just a matter of play-acting, they are manifestations of God, and evidence of Vishnu’s grace.

I don’t do a lot of gaming, but I’m pretty sure that the avatars that appear in a gaming context are typically more powerful and/or more attractive than their users. The opposite is the case with Vishnu’s avatars. Vishnu is said to be vast, with unlimited presence and influence that is beyond our comprehension. The avatar is only a small portion of Vishnu, designed to interact with humans on earth. When Vishnu descends as an avatar, it is as if he is reaching his hand down: the hand is the avatar, and it is the god, but it is not the whole god. Avatars are super-human, but they offer only a glimpse of the incomprehensible size and glory of Vishnu.

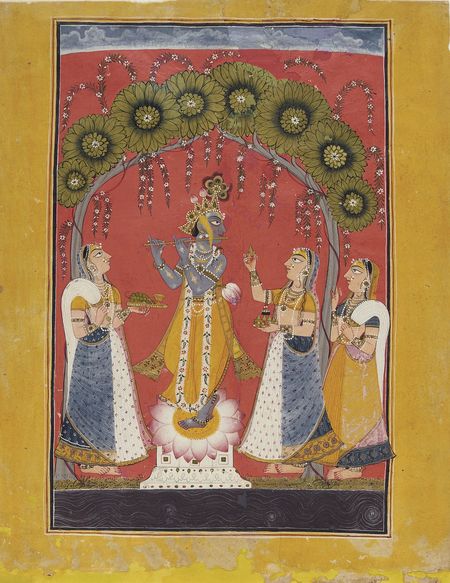

Avatar or something more? Krishna is sometimes removed from lists of avatars because he is thought to be greater than that: his devotees consider him a god in full. Krishna Fluting for the Gopis, page from an illustrated Dashavatara series. Northern India (Punjab Hills, Mankot), circa 1730. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 10 1/4 x 8 in. (26 x 20.3 cm). Collection of Catherine and Ralph Benkaim

Playing at avatars is a way of pretending to have powers similar to that of a god, but it is simply a matter of pretending. At some point in the future, it may actually be possible for humans to take temporary occupancy of new bodies. But even if we become big and blue and can communicate with flying horses via organic extension cords we will never be the equivalent of Vishnu’s avatars, who are, after all, divine.

Joan Cummins is the Lisa and Bernard Selz Curator of Asian Art at the Brooklyn Museum. Joan received her Ph.D. in 2001 from Columbia University. Prior to coming to Brooklyn, Joan served as Assistant Curator of Indian, Southeast Asian, and Himalayan Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Her most recent book is an introduction to Indian painting, published in 2006 by the MFA, Boston. Joan was a Research Associate in Brooklyn's Department of Asian Art from 1991-1993.