How about a nice game of 3D printed chess?

Earlier this year, we started exploring how 3D printing could enhance the visitor experience and began by introducing it on that month’s sensory tour. In addition to tours, we also host film screenings and as my colleague Elisabeth mentioned, this Saturday, September 28th we’ll be hosting a special screening of Brooklyn Castle, a film about a local school with a talented chess team that crushed more chess championships than any other school in the US. Since the screening also includes some chess playing outside the film, we figured it would be great to tie that into the context of the museum’s collection by curating and scanning our own 3D printed chess set.

Since April we’ve learned quite a bit about what makes an ideal scan and have spread that knowledge to our resident camera wizard, Bob Nardi, who I teamed up with for this project. We already had scans of the Lost Pleiad and the Double Pegasus, so we added them into the mix as the Queen and Knight, respectively. We also found the best candidates for the remaining pieces:

- Pawn (Egypt): Lion-Headed Gaming Piece

- Rook (New York): Rook [from a Wedgewood chess set]

- Bishop (Japan) : Emma – o, King and Judge of Hell

- King (Egypt): Senwosret III

We worked with our conservation staff to get access to the pieces which weren’t on view, including the roughly 3,000+ year-old Egyptian gaming piece Bob and I were a little nervous around. Using the same software combination of 123D Catch and Meshmixer, the scanned models were then generated and cleaned up and made watertight for printing.

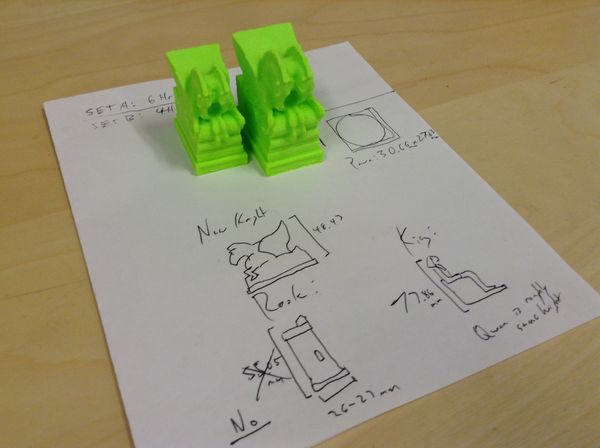

Having the 3D models ready to print, I worked on resizing them as chess pieces, making sample prints with some unsightly lime-green PLA we had laying around. Chess pieces have been remixed a lot over it’s history, varying from the small magnetic sets you would find in travel stores to the more elaborate Frank Gehry set. By and large there’s no universal standard for the size and proportions, but the US Chess Federation has some guidelines on the proportions relative to the board which were [partially] adopted in the final design of the set.

In the past, we’ve only printed pieces on a one-by-one basis. Since there’s 16 individual pieces to a chess set, that method quickly became impractical. Using the software for our Cube printer, we were able to add multiple models onto the platform and have the software automatically space them out. Marveling at the efficiency of this plan I made a test run and walked into the room our 3D printer resides in only to find that I made glitch art.

The aforementioned room is generally great due to it being more or less soundproofed from the rest of the office, but due to other equipment which share the space, it’s kept at a crisp 60F degrees. Since there’s not much movement happening in the room’s air that doesn’t tend to affect the prints, but it does seem to make the glue used to stick the prints to the platform and the plastic web between the pieces when they’re being printed stiffen faster, so some individual pieces would be just attached enough to each other to cause them to be yanked off the platform mid-print and eventually turn into Katamari Damashi.

The aforementioned room is generally great due to it being more or less soundproofed from the rest of the office, but due to other equipment which share the space, it’s kept at a crisp 60F degrees. Since there’s not much movement happening in the room’s air that doesn’t tend to affect the prints, but it does seem to make the glue used to stick the prints to the platform and the plastic web between the pieces when they’re being printed stiffen faster, so some individual pieces would be just attached enough to each other to cause them to be yanked off the platform mid-print and eventually turn into Katamari Damashi.

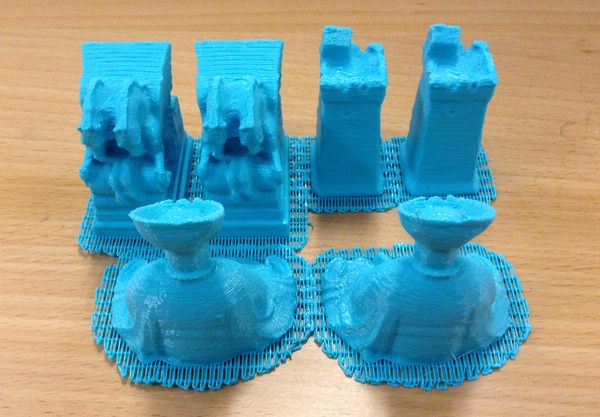

I managed to work around the temperature issue by turning on the raft option in the Cube Software settings. A raft in this case is a grid which is printed on the platform before the models are printed on top of it.

A raft keeps smaller pieces from detaching from the platform since it expands it’s connection to the platform beyond its otherwise tiny base size. The grid needs to be manually cut off around the edges after the print is complete, but that’s usually a quick process akin to peeling or shucking a really plasticy fruit or veggie.

After peeling it makes for a nice set ready to be shipped a whole three floors down! Sadly, I won’t be on this side of the Atlantic on Saturday due to other fun stuff, but if you want to see 3D printed chess in action, stop by and have fun in my place!

Just like our previous scans, we’re releasing the latest models under a Creative Commons license which you can download and print on your own 3D printer.

Download all models used in our chess collection (CC-BY-3.0) on Thingiverse

David Huerta was a Web Developer at the Brooklyn Museum from 2011-2016. Aside from helping maintain and improve the museum's website and mobile apps, he experiments with new technologies to investigate their potential in the museum experience. Currently, he co-organizes Art Hack Day, a part-hackathon, part-happening which brings artists and hackers together for 48 hours to build a pop-up exhibition. Before arriving in New York, he was one of the founding members for HeatSync Labs, an Arizona hackerspace which brings makers, tinkerers, and the occasional futurist together to build things and teach others how to do the same.