Opening the Gate

Clearing the Taharqa Gate is one of the season’s main goals, a goal we achieved, at least in part, this week: the north wing of the gate is visible from top to bottom, along with some of the ancient paving. On the left you are looking from the east end to the west. On the right, the arrow (indicating north) points at the original pivot for the gate’s door. The darker areas of stone were buried until this year.

Earlier in the week, we discovered that the limestone south jamb of the door in the wall running across the gate is a re-used block inscribed on both the east and south sides. You can see the inscription on the east face in the photo on the left. You can also see how fragile and fractured the block is. Removing the dirt from the inscribed surfaces without causing further damage calls for skill and patience, both of which Khaled (right) has in abundance.

Jaap and Khaled discuss the block and its texts (left), which Jaap copies as they are revealed (right). The copying is complicated by the fact that the block is upside down as well as badly fractured.

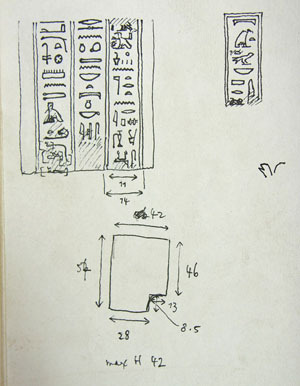

By week’s end both faces of the block are fully visible (left), although more conservation needs to be done before the block can be moved safely. On the right are Jaap’s notes (now part of the Expedition’s records) showing the dimensions of the block and both inscriptions.

And here are texts themselves, shown in their proper orientation. The inscription on the east side (left) is the top of a column of text that starts with a sign for heaven followed by “Great Mut, Mistress of Isheru” (the precinct’s sacred lake), one of Mut’s most common titles. The inscription on the south side (right) is part of an offering text in which Montuemhat offers cool water and wine to the goddess. Montuemhat, a powerful official under Taharqa, was responsible for a great deal of work in the Mut Precinct. This block may have come from a chapel he built within the precinct.

Two weeks ago we showed a photo of Bill and me inspecting a decorated block half-buried in dirt south of the Taharqa Gate. The arrow in the left photo points to the block, which became more visible as we began clearing the area this week; it is one of a number of blocks fallen from the gate and shows the lower part of a kneeling hapy figure (right), a type of “Nile” god that frequently represents fertility.

Pairs of kneeling hapy figures shown wearing the emblematic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt often decorate temple gateways, where they symbolize the unification of the country. On the west face of the Taharqa Gate’s north wing (left), such a pair supports a platform on which stand Amun and Taharqa. The king is on the left, entering the gateway where he is welcomed by Amun. On the south wing (right) they support a goddess welcoming the king. Only the feet of the goddess (surely Mut) remain in place.

We are in something of a quandary here: where does the newly-found hapy figure belong? Both pairs on the west faces of the gate are complete, and the east faces of the gate are too narrow for a pair of kneeling hapys on this scale. Did the interior of the gate’s wings once show a single hapy figure holding offerings? We may never know.

A particularly pleasant event this week was the arrival of Dr. Benson Harer on Saturday. Ben is a retired physician with a long-standing interest in Egyptology who has been a member of the Mut expedition for many years. I gave him a tour of our work this season (left) before he got down to work drawing pottery. It’s not glamorous work (actually, very little about archaeology is glamorous) but it is important and Ben, with his surgeon’s skilled hands and patience, does a terrific job.

The northern part of the area north of the Mut Temple has been pretty featureless so far. This week, however, it got more interesting, if somewhat confusing. The photo on the left, a view to the south, shows the remains of a mud brick wall (behind the red and white meter stick) that runs partway across the area. The wall is cut at the east end by an odd-shaped pit filled with broken stones, one of which (at the right end of the heap) turned out to be a large piece of a granite relief showing the foot of a god on a pedestal, both painted red (right). To the north (foreground, left photo) is another large pit. Both pits are filled with a very fine grayish ash that, in fact, is widespread across the area.

Just below the surface in the northern pit, we found two column drums that clearly join (left). When they were being excavated, the earth to their south collapsed, revealing the remains of a large animal hole, visible behind the column drums in the photo on the right. As we discovered a few years ago, this whole area was riddled with extensive animal dens. It may be that most of the pits in this area are actually the lowest levels of these dens.

Here are the column drums reunited. It’s not uncommon for sections of columns to be composed of two semi-circular blocks of stone rather than a single round block; that is the situation here. When complete, this column showed two scenes of a king offering to a deity. Parts of both kings are preserved (right), each with a text behind him that reads “like [the sun-god] Re forever”. The photo on the left shows all that remains of one of the gods: a leg and a hand holding a scepter.

Two distinct styles are present on this column. The heavy musculature of the king’s legs is characteristic of the art of Dynasty 25, while the less detailed carving of the god’s leg is more Ptolemaic in style. Another mixed Kushite-Ptolemaic column drum was found some years ago with the head of a Ptolemaic king offering to a Kushite-style Amun. It is possible that when the Ptolemies renovated parts of the Mut Precinct they simply recarved portions of certain columns rather than replacing them entirely.

The work on Chapel D is coming along as well. By Tuesday, the west wall of the first room had been dismantled down to its foundations, which were in good condition (left). The chiseled line you can see running the length of the foundations was cut by the original architect to show builders where to set the outer face of the wall; it helps our masons, too. By Thursday, we had put what is left of the blocks of the first course back in position (right), and the masons had begun to build up the missing portions with new sandstone. The plastic sheeting under the blocks isolates the wall being rebuilt from ground water.

With a new foundation laid for the wall west of the chapel’s door jamb (left), Mohamed Gharib and Tarek could begin the painstaking task of putting the wall back together (right). Since the original foundations are gone, they have to take great care to be sure the blocks that remain are aligned properly both horizontally and vertically.

We still enjoy watching the birds at the site. This hooded crow very kindly posed for Mary early one morning. Cattle egrets (right) are usually seen in fields, but this one seems to find our site attractive; it has hung around for several days and is very cooperative about being photographed.

Monday’s dawn was spectacular, whether looking east from our hotel room window (left) or west to the mountains across the Nile.

Richard Fazzini joined the museum as Assistant Curator of Egyptian Art in 1969 and served as the Chairman of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art from 1983 until his retirement in June 2006. He is now Curator Emeritus of Egyptian Art, but continues to direct the Brooklyn Museum’s archaeological expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak, a project he initiated in 1976. Richard was responsible for numerous gallery installations and special exhibitions during his 37 years at the museum. An Egyptologist specialized in art history and religious iconography, he has also developed an abiding interest in the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. Well-published, he has lectured widely in the U.S. and abroad, and served as President of the American Research Center in Egypt, America’s foremost professional organization for Egyptologists.