The First Harvest in the Wilderness

Valerie Hegarty’s evocation of Asher B. Durand’s 1855 painting The First Harvest in the Wilderness in her benefit print for the 1stfans program adds another chapter to the painting’s already illustrious history. Its story begins in 1855, when the Brooklyn Institute—the predecessor to the Brooklyn Museum—commissioned a work from Durand to add to its newly conceived Gallery of Fine Arts. The money for this painting, as well as the idea for a permanent gallery, came from the late Augustus Graham (1775-1851). A prominent local businessman and philanthropist, Graham had been actively involved in charitable institutions devoted to the edification of Brooklyn’s citizenry, including the Institute (established 1843) and its forerunner, the Apprentices’ Library Association (founded 1824). Upon his death in 1851, he bequeathed a large sum to the Brooklyn Institute with the stipulation that a portion of the money be used for the purchase of art by living American artists for the Institute’s picture gallery. This stipulation was progressive and prescient at a time when few civic institutions had art collections and many patrons viewed American art as inferior to European art.

Asher B. Durand (American, 1796-1886). The First Harvest in the Wilderness, 1855. Oil on canvas, 31 5/8 x 48 1/16 in. (80.3 x 122 cm) Frame: 43 1/2 x 59 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. (110.5 x 151.1 x 12.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Transferred from the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences to the Brooklyn Museum, 97.12

For its inaugural purchase with the Graham bequest, the Brooklyn Institute sought out one of the nation’s leading artists Asher B. Durand (1796-1886). At this time, Durand was the dean of American landscape painters known as the Hudson River School and president of the National Academy of Design in New York. As a sign of support for the Institute, he agreed to accept the Brooklyn commission for $175, a sum far smaller than his usual asking price.

At first glance, The First Harvest in the Wilderness, which was hanging on the Institute’s walls by September of 1856, is an allegory of the nineteenth-century concept of Manifest Destiny. This belief held that the United States was destined to expand across the entire continent. (Many Americans viewed westward expansion as the inevitable progress of a divinely favored and culturally superior nation, although it resulted in the exploitation of natural resources and the often violent subjugation of native peoples.) Durand’s picture depicts the softer side of Manifest Destiny in the form of a pioneer family domesticating the frontier through settlement and agriculture. We see their homestead in the center of the painting in the midst of a rugged landscape of forests and mountains-the bright light that shines upon this clearing not only draws the viewer’s attention to the homestead, but also symbolizes divine approbation. While a man harvests a field of wheat (dotted with the stumps of trees he has felled), his wife stands before their snug log cabin (built from felled trees) and cows and horses graze in their pens. Durand suggests that the pioneers enjoy the fruits of their labor-an idyllic and bountiful existence on the frontier full of promise of future rewards.

Asher B. Durand (American, 1796-1886). The First Harvest in the Wilderness (detail), 1855. Oil on canvas, 31 5/8 x 48 1/16 in. (80.3 x 122 cm) Frame: 43 1/2 x 59 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. (110.5 x 151.1 x 12.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Transferred from the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences to the Brooklyn Museum, 97.12

A closer examination of The First Harvest in the Wilderness reveals that this vision of national progress also had particular, local significance for Brooklyn. The large rock in the right foreground of the painting is inscribed with the name “GRAHAM,” a clear reference to Augustus Graham, the Brooklyn Institute’s benefactor whose bequest funded this commission. This rock serves as a rustic gravestone memorializing the man. In addition, its prominence in the composition symbolizes Graham’s important role in advancing civilized pursuits in another kind of wilderness-the American art scene. One reporter for the art journal The Crayon was quick to pick up on the painting’s analogy between progress on the frontier and progress in the arts. He wrote:

The sentiment of the picture is also in keeping with the circumstances belonging to its production. The field of Art is, in the country, but just emerging into the reality of a clearing, upon which the sun of encouragement does shine, if it gleams from clouds and is surrounded by shadows. As an illustration, Mr. Graham may be considered the pioneer in the wilderness, and all honor be to his memory for being the first to make a clearing.[1]

In other words, just as the settler transforms the inhospitable frontier into farmland, so too did Augustus Graham cultivate the arts in the cultural fields of America. Although Graham’s vision for the Brooklyn Institute took decades to accomplish-shifting administrative priorities and declining financial fortunes hampered the plans for a permanent gallery in the nineteenth century-his support helped to make American art one of the finest and foundational collections of the Brooklyn Museum.

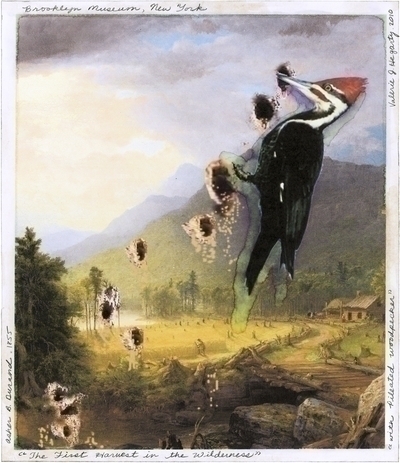

Valerie Hegarty. First Harvest in the Wilderness with Pileated Woodpecker, 2010. 10 x 8 in., ed. of 200. © Valerie Hegarty. Image courtesy of the artist and 20×200 | Jen Bekman Projects

Given Graham’s commitment to living American artists, it seems only fitting that Valerie Hegarty, an American artist of today, pays tribute to Durand’s The First Harvest in the Wilderness—the first painting funded by the Graham bequest.

[1] “Domestic Art Gossip,” The Crayon 3, no. 1 (January 1856): 30.

Karen Sherry joined the Museum in 2003 as project coordinator for the Luce Center for American Art’s Visible Storage ▪ Study Center, a publicly accessible storage facility containing more than 2,000 works of art. In her current position since 2005, she has organized several special exhibitions from the Museum’s renowned collections of American art, including shows on plein-air sketching, Japonisme in American graphic arts, Francis Guy’s early Brooklyn scenes, and, with Teresa Carbone, American landscape watercolors. Prior to coming to the Museum, Ms. Sherry worked as a research assistant at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Brandywine River Museum, and as co-curator of an exhibition on John Sloan’s graphic works at the Delaware Art Museum. She has also taught art history at Pratt Institute, University of Delaware, and Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. She earned a B.A. degree from Boston University and an M.A. from University of Delaware, where she is currently completing her Ph.D. Among the honors she has received are fellowships from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Winterthur Museum.