The End of the Season

In this last dig diary for 2010 I want to acknowledge the hard work, skill and patience of some of the most important members of our team: the Egyptian technicians without whom the work would not be possible. This year we were fortunate to have Abdel Aziz Farouk Sharid, Mahmoud Abbadi, our invaluable foreman Farouk Sharid Mohamed, Ayman Farouk Sharid and Abdullah Moussa, all of whom have worked with us for many years. Excavation ended on Monday, and here is some of what was accomplished this season.

Through dogged determination and skill, Mahmoud finally found the southeast corner of the Tuthmoside enclosure wall. Centuries of erosion have created the illusion that the wall slopes down fairly steeply to the east. At the north end of the east face we found a surface of packed earth and stone chips. As mentioned last week, the Tuthmoside wall may have been cut through at this point in the Ptolemaic Period to allow access from Chapel D to the sacred lake.

When the season started, we suspected there was a corridor west of the Taharqa Gate wall. Here it is, seen from the south (left) and north.

From the enclosure wall the relationship between Chapel D and the Taharqa Gate is very clear. The chapel was built against the gate’s north wall (right), uncovered by Ayman. From this vantage point you can also see the west end of the Mut Temple’s 1st Pylon, with its late extension (rear left), the Taharqa Gate and its south wall (right) and the sacred lake in the background.

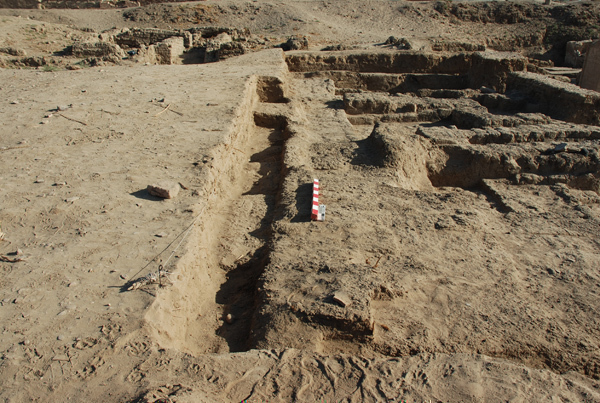

The paving of the approach to the Taharqa Gate, seen from the southwest at the end of the season. The wall forming the south side of the approach (right foreground) is preserved to a greater height here than further east, where Ayman was working.

The wall just mentioned is still in place on the right in this photograph, but we have excavated the eastern section down to the level of the 25th Dynasty paving. A surface slopes up to the left (east); this was probably an early walking surface associated with the paving. Over it lies the thick build-up of stone-filled earth with the line of baked brick on top. This stony debris may be have been intentionally dumped to create an even surface for later buildings.

The north-south portion of the odd baked brick feature whose northwest corner we found under the baulk last week runs the full length of area where we have been working. In the process of excavating this portion we confirmed that all of the mud brick structures above it (upper left) were built on layers of earth and ash that at one point ran across the whole area.

At its south end the baked brick line is somewhat broken, as you can see here in this view to the south, but it continues almost to the baked brick building that sits on top of the remains of the Tuthmoside enclosure wall. Despite having found the walls’ full extent, we still don’t know what they were for. Only a few courses remain, but they are solid and so the feature is not a drain or water conduit.

Where Abdullah has been working we now have the west face of the wall that runs from the south limit of our excavations to the Taharqa Gate boundary wall. We have found more brick running west from this long wall, some of which is visible in this shot. We are obviously dealing with a large building or complex, but still do not have enough information to be able to say what the building is, although the pottery suggests it was built in the Roman Period. Archaeology can be frustrating.

The restoration of Horwedja’s healing magic chapel continued through the end of the week. On Tuesday morning, the east wall of the chapel (left) still lacked its last block and the finishing coating for the modern stone, tinted to match the ancient stone, had yet to be applied. On the right is the completed wall on Thursday morning.

Cleaning the ancient cement and dirt from the underside of the lintel produced a surprise: the original emplacements for the chapel’s double doors and the line against which the doors closed. It is unusual for such a small chapel to have 2 doors.

On Thursday morning Mary took advantage of the early light to photograph the chapel’s facade, which is only clearly lit until about 8 am at this time of year. Despite its diminutive size (currently the smallest chapel standing at Karnak), the chapel is an important monument of its period.

The front of the chapel with its walls complete and the lintel in place. We thank Khaled Mohamed Wassel, Mohamed Gharib and their team for their hard work on this project.

We didn’t forget the sphinx from whose base the lintel came. We filled the gap with new stone that Mohamed Gharib is tinting to match the rest of the base’s blocks. On the right the finished product.

Once the excavating was finished we had time to try to answer a few questions about other parts of the site. One was the name of the king whose badly eroded torso and cartouche are on a re-used block at the south end of the west wing of the Mut Temple’s 1st Pylon. I was fairly certain it was a Tuthmosis, but we had never been able to get a legible picture of the cartouche: the block is awkwardly placed for photography and only gets direct light in the afternoon. Balancing rather precariously on the steep slope of the pylon, Jaap and Mary were able to use a mirror to cast a raking light that finally made the remains visible and I was finally able to get a picture. The cartouche clearly shows an ibis on a standard (right), which means “Djehuty”, the first element in the name Tuthmosis (Djehuty-mes).

Strong winds on Friday wreaked havoc on our workspace, knocking down both shelters. We put them back up Saturday, but the weather remained windy, threatening to bring them down on our heads. Blue cord and a couple of strategically placed stones solved the problem, and the tents survived to the end of the season.

The last few weeks of digging produced a couple of interesting objects. On the left is a stamped amphora handle, probably from an amphora produced in Rhodes. Since goods were shipped all over the Mediterranean world in such amphorae, they are very useful for dating the contexts in which they are found. On the right is a fragment of a fine glazed pottery bowl decorated with a figure that is probably Nemesis, with her raised paw on the wheel of fate (of which only the top is preserved), which she controls. Nemesis is a deity important to archaeologists.

Richard Fazzini joined the museum as Assistant Curator of Egyptian Art in 1969 and served as the Chairman of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art from 1983 until his retirement in June 2006. He is now Curator Emeritus of Egyptian Art, but continues to direct the Brooklyn Museum’s archaeological expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak, a project he initiated in 1976. Richard was responsible for numerous gallery installations and special exhibitions during his 37 years at the museum. An Egyptologist specialized in art history and religious iconography, he has also developed an abiding interest in the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. Well-published, he has lectured widely in the U.S. and abroad, and served as President of the American Research Center in Egypt, America’s foremost professional organization for Egyptologists.