Name That Bronx Zoo Cobra? “Wadjet” Of Course!

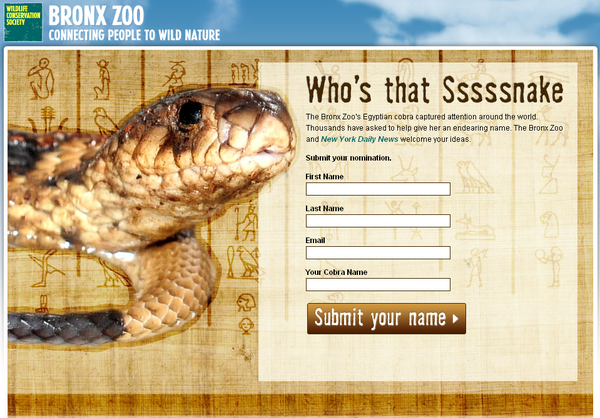

Last Friday, my husband came home with a New York Post article announcing that the young female cobra who escaped from the Bronx zoo, thus becoming probably the most famous snake in the New York area, if not the whole country, had been found and that a contest to name her is now being held. Distractedly looking up from my work, I replied: “That’s silly. It is perfectly obvious that her name should be Wadjet, after the cobra goddess of Lower Egypt!” and proceeded to tell him why at length.

Since then the naming contest has made the pages of The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times and I see that other “Egyptologically-minded” readers have already suggested the name Wadjet. Unfortunately, this name does not appear to be a “front-runner” among suggestions so far, at least according to the Times.

As it happens, last year I was invited to write an entry on the goddess Wadjet for a forthcoming Encyclopedia of Ancient History, which naturally required lots of enjoyable research. I would therefore like to point out why the name of Wadjet seems so entirely appropriate to me.

Head of Hatshepsut or Thutmose III, ca. 1479-1425 B.C.E. Granite, 10 3/8in. (26.3cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 55.118. Creative Commons-BY-NC

The goddess Wadjet (also called Wadjyt, Ouadjet, Uto, and Edjo in Egyptological literature) appears in ancient Egyptian mythology from the earliest times. Her name means something like “The Green or Fresh One” or “She of the Papyrus Plant.” Associated with Lower Egypt, she is often paired with the goddess Nekhbet of Upper Egypt; together they are the Two Ladies in the second title of the king, representing the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. In her earliest form, as a cobra, Wadjet is also the uraeus snake that appears on all Egyptian royal headgear, performing a protective function.

Statue of Wadjet, 664 B.C.E. – 332 B.C.E. Bronze, 20 1/2 x 4 7/8 x 9 1/2 in. (52.1 x 12.4 x 24.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 36.622. Creative Commons-BY-NC

Wadjet’s embodiment as a fierce, spitting cobra leads to her inclusion in a group of goddesses, who are all variously identified with The Eye of Re in ancient Egyptian religion. Many of the other goddesses in this group are often depicted with lion heads and therefore Wadjet too could be shown with a lion head from the New Kingdom period on; we have a fine example of this here at The Museum.

We know from ancient Egyptian mythology that The Eye of the sun god Re was envisioned as a goddess, his divine daughter. The Eye protected Re from his enemies but she also had an angry, destructive aspect. One myth concerning The Eye of Re certainly makes me think of the Bronx Zoo cobra.

This story survives in a number of different versions, often incomplete, and because we don’t have an ancient title for it, is usually referred to as “The Distant Goddess,” “The Wandering Eye,” or “The Myth of The Eye of The Sun.”

As so often happens in even the best divine families, Re and his daughter The Eye have a big fight, although none of the versions of the story specify the cause of their disagreement. The Eye runs away, storming off to the desert or other distant, wild regions, where she sulks. To the ancient Egyptians, the desert and other wild, uncultivated regions represented the chaos outside the ordered Egyptian world, personified by the goddess Maat. Although the Bronx Zoo cobra never actually left the building, she did run away from the ordered world of her cage, causing disorder by her absence.

Re discovers that he misses his Eye and that her absence threatens his safety and indeed that of the cosmos. So he sends another, more junior deity, in some versions the god Thoth, to find her, appease her, and persuade her to come home. Her return is greeted with great rejoicing, celebration, and relief—just as that of the wandering young female cobra from the Bronx Zoo has been.

Madeleine Cody is a Research Associate for Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Middle Eastern Art. She has a B.A. in Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology from Bryn Mawr College, an MA in Egyptology from Brown University, and is currently completing her Ph.D. in Egyptian and Ancient Near Eastern Art and Archaeology at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. She has worked on excavations in Italy, Yemen and Egypt. Since coming to the Museum in 1997, she has been involved with numerous projects and assisted the late James F. Romano, Project Director, with the second phase of the reinstallation of the Egyptian Galleries, which opened in 2003. With Jim and Richard A. Fazzini, she is a co-author of Art for Eternity: Masterworks from Ancient Egypt (Brooklyn, 1999) and has written about other Egyptian objects from the Museum’s collection. Currently, she is working with the ancient Middle Eastern Art collection, her other area of expertise. She is co-curator of the Herstory Gallery exhibition, The Fertile Goddess, (December 19, 2008 – May 31, 2009).