Architectural Fragments from Coney Island’s Steeplechase Park

On June 19, Coney Island will celebrate the beginning of summer with the annual Mermaid Parade, a colorful and highly unique procession of costumed mermaids, Neptunes, and sea creatures, marching bands, floats, antique cars, and the like. Because for many New Yorkers summer has always been associated with Coney Island, I’d like to celebrate the season by sharing some of the Brooklyn Museum’s art works from Coney Island—the Museum’s roaring zinc lion and pair of cast iron lampposts, both from the old Steeplechase Park.

Hugo Haase (German, 1857-1933). Lion, from the El Dorado Carousel, Coney Island, Brooklyn, ca. 1902. Zinc sheeting, Mounted: 82 x 36 x 69 in. (208.3 x 91.4 x 175.3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Frederick Fried, 66.251.1. Creative Commons-BY-NC

One of the earliest art works to enter the Museum’s Sculpture Garden collection, and perhaps one of the most popular, is the roaring lion, installed over the rear staff entrance to the Museum, ready to pounce on those who enter. The lion had a long history before coming to the Museum in 1966. He was originally designed as one of a trio that pulled a chariot atop the entrance pavilion to the ornate El Dorado Carousel, a popular attraction at Coney Island for over 50 years.

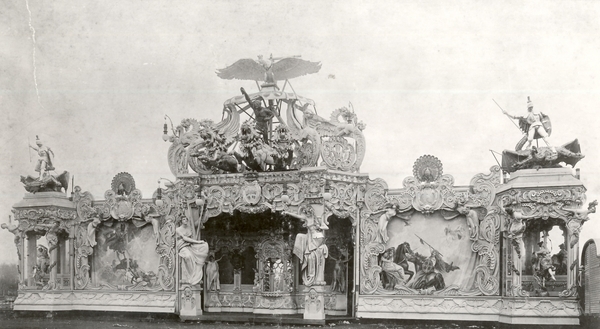

Image from Carol A. Grissom, Zinc Sculpture in America 1850-1950 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2009), p. 427.

This elaborately gaudy gateway was decorated with life-size female figures playing harps or floating through the clouds and with painted curtains depicting women warriors on horses. The central gateway was surmounted by the chariot, and life-size figures of St George slaying the dragon topped the niches at either end. Like the lion, the rest of the façade was made of formed sheet zinc and painted in bright colors. Research has determined that the lion may have originally been painted a gold color with bronze metallic paint and illuminated with electric lightbulbs in its eye sockets and emitted sparks from its mouth.

The elaborate and ornate carousel itself was composed of three separate platforms, each rotating at different speeds. The innermost was a throne room surrounded by life-size angels with trumpets; the outer and inner tiers had beautifully carved chariots. The platforms were adorned with a menagerie of creatures—horses, pigs, ducks, eagles, dolphins, and cupids–all made of hand-carved wood and surrounded by Art Nouveau paintings, mirrored posts, and 6000 flashing lights. Inside was a four-ton band organ manufactured by A. Ruth und Sohn in Waldkirch, Germany.

The carousel was built in 1902 by Hugo Haase of Leipzig, a successful German amusement park ride manufacturer and bridge builder. In 1910, it was purchased by John Jurgens for the exorbitant price of $150,000 (plus $30,000 custom fees) and installed near Dreamland Park on Surf Avenue. It was only one of several independent carousels in Coney Island, but according to carousel expert Frederick Fried, it was “the most spectacular carousel America had ever seen.”

On May 27, 1911, Dreamland Park was destroyed by a huge fire and was never rebuilt (the New York Aquarium, founded in 1896 at Castle Garden in Battery Park, has occupied that site since 1957). The fire also damaged the carousel but not much. It was purchased and repaired by Steeplechase Park’s owner George C. Tilyou, who moved it indoors to his fireproof building the Pavilion of Fun. The carousel’s sheet zinc sculptural façade was then relocated as the corner entrance to Steeplechase on Surf Avenue for the next decade. When the façade was demolished in 1923, the three lions were removed and reused elsewhere in the park.

In 1965, Tilyou’s descendants sold the park to developer Fred Trump (Donald’s father), who demolished the park before it could gain landmark status. In 1968, unable to build his apartment complexes because of zoning regulations, Trump sold the land to the city. Since 2001 it has been the site of MCU Park (formerly Keyspan Park), the home of the Brooklyn Cyclones baseball team.

What happened to the carousel and lions? When the park was demolished, most of the amusement rides were put in storage and eventually sold. The El Dorado carousel was purchased for the 1970 Osaka World’s Fair, and is currently in use at the Toshimaen Amusement Park in Tokyo. The El Dorado lions were purchased by private collectors, including Frederick Fried, who donated this lion to the Brooklyn Museum in 1966.

Brooklyn Iron Foundry. Lamp Post, one of two, from Steeplechase Park, Coney Island, Brooklyn, ca. 1900. Cast iron, 140 in. (355.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, 66.254.2. Creative Commons-BY-NC

The museum also purchased a pair of lampposts from Steeplechase Park, which are now installed in the Sculpture Garden. These two street lights, manufactured by the Brooklyn Iron Foundry around 1900, are designed with a central globe encircled by four hanging globes. In 1984 the city used the museum’s historic lampposts to cast reproduction street lights (models BB12 and BB14) for use in a renovation of Union Square.

Margaret Stenz, Curatorial Associate in American Art, is currently heading a curatorial review of the Sculpture Garden/Architectural Fragments collection and co-curating a traveling exhibition of the Museum's American modernist paintings and sculpture. In 2005, Dr. Stenz organized a special exhibition on the graphic works of the Robert Henri circle, and has contributed research and editorial assistance to several exhibition catalogues and permanent collection catalogues. She joined the museum in 2002 as the Andrew Mellon Research Associate in American Art, and shortly after she completed her Ph.D. in art history at the City University of New York Graduate Center. Previous to joining the Brooklyn Museum, Dr. Stenz worked at the New Britain Museum of American Art, Beacon Hill Fine Arts, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and taught art history at Baruch College and the University of Kansas. Among the honors she has received are fellowships from the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Jewish Foundation for Education of Women.