Making Papyrus in the Conservation Lab

Before we began treatment on the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose papyrus scroll, the staff of the paper conservation lab decided to make our own papyrus sheets. As with any conservation treatment that we do, it is important to have a good understanding of the materials and techniques that went into creating the original so that we are accurately equipped with the knowledge necessary to treat it. We tried to emulate the process used by the ancient Egyptians as closely as possible using the materials and tools available to us. The first thing that is necessary to make a sheet of papyrus is a papyrus plant.

Papyrus is a perennial freshwater plant which favors marshes and swamps. It grows best in shallow water along the edges of sheltered fresh water bodies, which is why the banks of the Nile are an ideal location for growing papyrus. Fortunately, we are located next door to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, where papyrus grows in the Aquatic House.

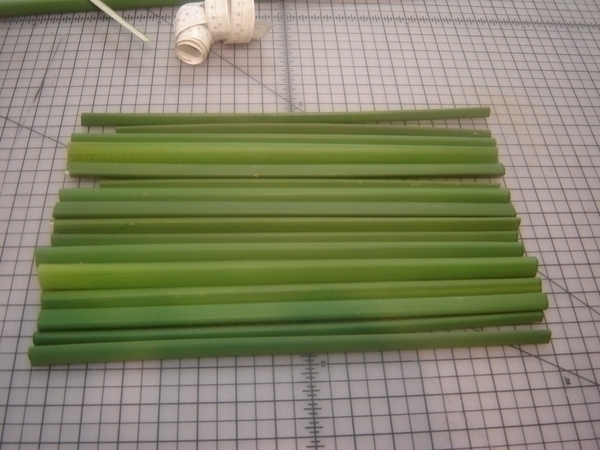

We contacted the garden and they agreed to let us have a few stalks. Medium-sized stalks were selected for their uniform age and size and they were cut just above the bottom. We brought the stalks back to the paper lab and cut them down further using a simple kitchen knife. We decided to use the middle portion of the stalk to ensure consistency in thickness and in length.

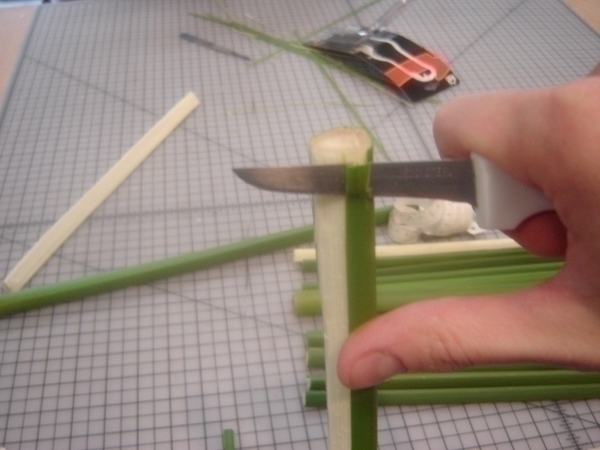

We peeled away the green rind using a simple, small sharp knife blade.

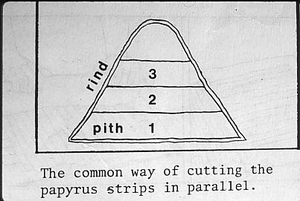

We tried a variety of tools to thinly slice the stalks into strips including small sharp razor blades, and various kitchen utensils such as vegetable peelers and food slicers. We found that a simple blade was the best tool to achieve the thinnest strips. We sliced through each stalk using the parallel cutting method.

We did encounter some difficulty in slicing the strips as thinly as we wanted, and achieving uniform thinness among all of the strips. This may be due to our skill level in slicing, the tools available to us, or with these particular stalks of the papyrus.

The strips were soaked in water for 24 hours to swell the plant cells and fibers and allow water to fill the air spaces. This image shows them soaking in a tray of water, weighted down under a sheet of Plexiglas and some small brass weights to ensure that the strips remained submerged.

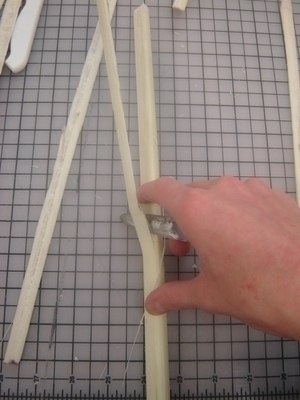

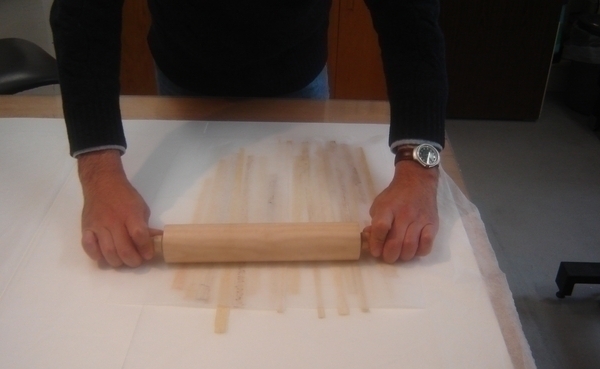

The wet strips were removed from the water bath. We used a standard rolling pin to forcefully press the strips flat. At this point we observed a significant reduction in the thickness of the strips.

We returned the flattened strips to the water bath, and the process of soaking and pressing the strips was repeated several times over the course of a few days. At this point the damp, flattened strips were lined up side by side with the long edges of each strip slightly overlapping the next.

A second layer of strips was lined up side by side, on top of and perpendicular to the first layer, forming a two-layered sheet.

For a final press using extreme pressure, this sheet was placed into a wooden book press between sheets of blotter paper and flat wooden boards. It was left in the press for several days, switching the blotters several times, to ensure that the sheet was fully dried and completely flat. As described in Toni’s post, this extreme pressure causes any remaining hollow spaces and air ducts to compress and the plant fibers to interlock forming a very strong physical join.

After several days, the sheet was removed from the press. Our final product was dry and flat yet flexible, and the layers were well-joined.

Its appearance differs from that of ancient papyrus in many ways. The white color is the most notable difference; however it is believed that the color is similar to that of an un-aged sheet of ancient papyrus. Our sheet is also much thicker than most examples of ancient papyrus, perhaps owing to our method of slicing or pressing the strips.

Samples of ancient and modern papyrus have been examined by researchers using extremely high magnification called Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and these comparisons show a difference in the overall order, regularity and size of the plant cells. In the samples of ancient papyrus, the cells demonstrated a very regular pattern similar to chain mail, and in the samples of modern papyrus, these cells exhibit a similar order and regularity, but differ in cell size.

Both visual and microscopic differences such as these serve as a reminder that duplicating the methods and tools used by ancient Egyptians is a challenge. Trying to make papyrus ourselves gave us a much better idea of the structure of a sheet of papyrus and how it was done in ancient times, though all of the details to papyrus-making remain a mystery.

—-

This post is part of a series by Conservators and Curators on papyrus and in particular the Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sebekmose, a 24 foot long papyrus in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. This unique papyrus currently in 8 large sections has never been exhibited due to condition. Thanks to a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation, the entire papyrus is now undergoing conservation treatment. The conservation work is expected to last until fall 2011 when all 8 sections will be exhibited together for the first time in the Mummy Chamber. As each section is conserved, it will join those already on exhibition until eventually the public will see the Book of the Dead in its entirety.

Caitlin Jenkins is currently the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Paper Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum. She received her M.A. in Art Conservation from Buffalo State College in NY and before coming to the museum she held positions and completed internships in a variety of other conservation labs at institutions including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Northeast Document Conservation Center in Andover, MA, the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, NC and the Wilson Library, also in Chapel Hill. She received B.A.s in Art History and in Historic Preservation from Mary Washington College.