Many Hours for a Split Second

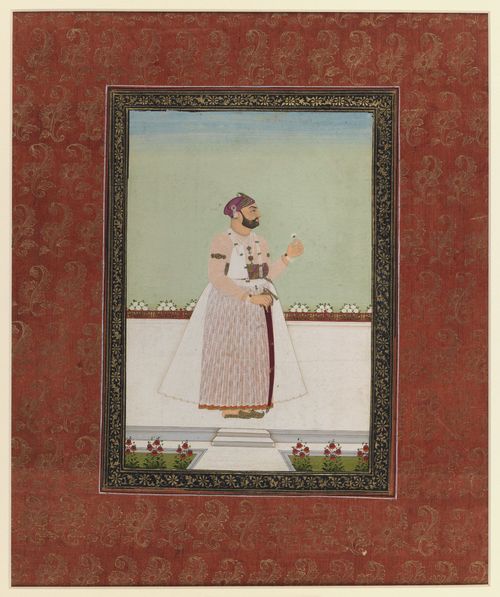

With the initiation of the project Split Second, Joan Cummins, Curator of Asian Art selected a very large number (185) of works from the Museum’s Indian Painting collection to post on our website for the Split Second survey. Both Conservator and Curator assessed this checklist to preemptively eliminate any works with condition problems requiring extensive treatment.

Works were brought into the Conservation Lab in late April.

Our time frame for conservation of the paintings was relatively short: images of the ~180 works were posted online in February and March. The data was assessed in April and 11 paintings were selected. Thus we had about 8 weeks prior to the exhibition to complete our examination of each painting and undertake any needed treatment and framing. We brought the works to the lab in late April for review.

A very common condition problem with Indian painting is paint instability. There are several reasons for this: these paintings are made from opaque watercolors, applied in many layers between burnishing and often thick dots of paint (impasto) are applied over the surface as decorative elements. These multiple layers and peaks of paint are subject to cracking, lifting and detaching.

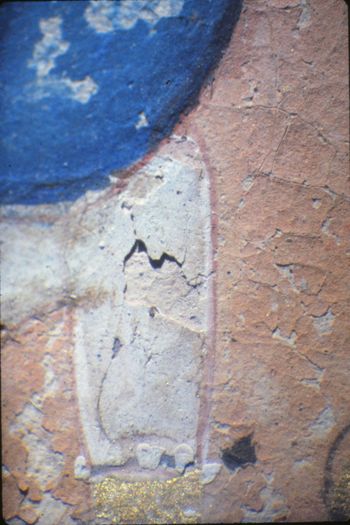

Photomicrograph showing small previous losses in the pink pigment as well as a lifting flake of white paint at the center.

Seven of the eleven works in Split Second had loose and flaking paint when examined inch by inch under the microscope. In this photomicrograph (left) you can see small previous losses in the pink pigment as well as a lifting flake of white paint at the center. Though it looks obvious at this magnification, paint instability is often only discovered with the aid of a microscope. If not secured, flaking paint can detach completely leaving a void. Usually the paint surrounding a void then becomes loose. Thus consolidation of loose and lifting paint using a variety of adhesives is critical.

Previous losses are usually accepted as part of the age of the painting in Indian miniature paints and the responsibility of Conservation is to prevent additional losses from occurring, rather than to cover up old losses. Sometimes, however, a decision is made by the curator and conservator to fill a previous paint loss; this was true in the case of Dhanashri Ragini (80.277.9).

Lastly housing each of the paintings in archival rag mats to accommodate the paint and support is considered. Note that Chandhu La’l (59.206.2) and the folio from the Qissa-I Amir Hamza (24.46) both have strong undulations in the sheet, (i.e. they do not lie flat as most of the other paintings do. This is because both are double sided and have multiple layers of paper, fabric etc. which naturally cause distortions).

Decisions can be made within a split second but conservation and preservation take much longer. Enjoy the exhibition.

Toni Owen is Senior Conservator at the Brooklyn Museum. She joined the staff in 1986 to help plan the Museum’s paper conservation laboratory. Toni received her Master’s Degree and Certificate of Advanced Study in Conservation from the State University of New York, Cooperstown, New York. Prior to the Brooklyn Museum Toni was a Mellon Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and from 1977 until 1985 she was head of Paper Conservation at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution.