Elvis is in the building

Elvis is at the Brooklyn Museum and not where you’d expect to find him—in the new installation of the Museum’s African galleries, African Innovations.

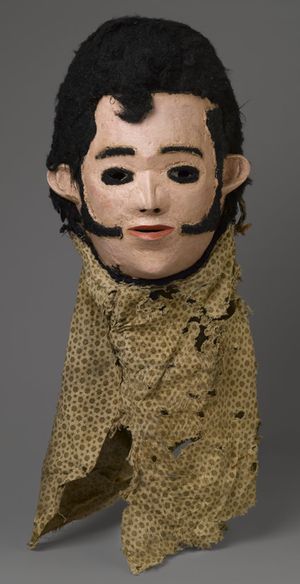

Elvis Mask for Nyau Society, ca. 1977. Wood, paint, fiber, cloth, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Gordon Douglas III, Frederick E. Ossorio, and Elliot Picket, by exchange and Designated Purchase Fund, 2010.41

Brooklyn’s Elvis is a ceremonial mask of the Nyau Society of the Chewa peoples, who reside primarily in central Malawi. The Nyau is a secret society that creates these masks for inclusion in ritualistic dances as part of initiation ceremonies, chief coronations and funerals. The masks often represent revered ancestral and animal spirits. They also have satirical themes and occasionally depict famous foreigners as a means to provide education on social and cultural values. This unique incarnation of a western cultural icon highlights a fascinating interaction between western and non-western societies.

The mask is hand carved from a single piece of wood with the eyes, mouth and nostrils pierced through. The face is painted with a thick application of pink paint. Synthetic hair defines Elvis’ characteristic pompadour hairstyle and sideburns as well as the eyes and eyebrows. Various textiles and burlap are attached around the neck.

Acquired by the Museum in 2010, Elvis wasn’t quite ready for the spotlight. The hair had been infested with insects, painted areas were dirty and flaking, and the textiles, believed to be original to the mask, were in tatters.

Upon its arrival in the conservation lab, the mask was monitored to determine that live insects were not present, and then it was thoroughly groomed to remove old insect casings and debris. Painted surfaces were lightly cleaned and stabilized. The textiles around the neck were reconstructed and secured around the bottom edge of the mask by stitching the original textile to a support backing of nylon netting—the same netting textile conservators use to stabilize our mummy collection. The netting provides support for the original fabric without altering the appearance.

The conservation of Elvis highlights how conservators approach the treatment of many ethnographic objects. The mask was not restored to what it may have looked like when it was first made. Instead, it was conserved to reflect the history of its use and to make it stable enough to be exhibited safely without further deterioration.

Elvis will be a featured in African Innovations opening August 12th—just in time for the 34th anniversary of the Elvis’ death. So if you can’t make it to Graceland this year, stop by the Brooklyn Museum.

Kerith Koss is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Objects Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum. She received her Master's Degree in Art History and Conservation from the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Before joining the Brooklyn Museum in 2008, she was a Smithsonian Post-Graduate Fellow at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Over the course of her conservation training, she has completed internships at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Field Museum in Chicago and the Shelburne Museum in Vermont and has assisted in hurricane recovery efforts at several local museums on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi.