Old projects, new projects

Jaap’s wife, Egyptologist Julia Harvey, arrived on February 15, completing this season’s small team. Julia has agreed to take on the pottery, with which she has considerable experience. She already has the first batches sorted and organized.

We finished work on the paving west of the Taharqa Gate early in the week and Mary got up on a ladder to photograph the results. As expected, some of the newly-exposed stone was badly decayed, but enough survives to show the course of the roadway.

Abdel Aziz’s square north of the Ramesses III temple is no longer boring. After about 1.2 m of clean earth, we began to encounter mud brick. By the end of the week, aside from a few shallow pits with stone, mud brick covered almost the whole square and we had found a line of baked brick along the west side. We are fairly certain that what we have now are the foundations either of the temple’s north enclosure wall or perhaps its pylon. Ramesses’ temple stood within its own mud-brick enclosure (remember, it was outside the precinct until the 4th century BC), of which only the west and south walls survive. The eastern wall seems to have been completely eaten away by centuries of flooding.

With the Taharqa Gate finished, we opened a new square north of Abdel Aziz to continue our search for sphinx bases. Ayman has encountered the same thick layer of wind-blown earth over broken stone. By the end of the week he was about 90 cm below the modern surface. At least some of the stone in this square seems to be larger and in better condition than in Abdel Aziz’s square.

Several years ago we rebuilt the west wing of the Mut Temple’s mud brick 2nd Pylon to a height of about 3 m to give visitors some idea of its appearance. Of the pylon’s sandstone gateway very little is left, as you can see. We have determined, however, that the two remaining inscribed blocks actually join, the lower one fitting to the left of the upper, although both are somewhat out of position now. We decided this season to put these two blocks back in place and started work on Tuesday.

Once the two blocks were removed we had to clean up the accumulated dirt, plant remains and deteriorated stone behind them (left). By the end of work Wednesday the debris had been removed, a new support for the blocks was well underway, the new construction conforming to the shape of the remaining ancient blocks. The 2 main pieces of the larger block are ready to be re-joined (right), with stainless steel rods ensuring that the join is secure.

Once the mastaba we built last week was dry, we began moving decorated blocks onto it. Some were relatively easy: large, but able to be moved by a few men using a wooden stretcher and stout straps. Hassan supervises the careful placement of such a block.

The beautifully carved block in the center of this picture was another matter entirely. Not only is it huge, but its lower surface has been both cut away and worn by time, making it difficult to balance. While it could be moved to the edge of the mastaba with a combination of siba (tripod and winch) and levers, it was too heavy for the siba to raise it to the top of the mastaba.

On Thursday morning Mahmoud Farouk, foreman of the work at Karnak (center) and an expert at moving large blocks, used a hydraulic jack, levers and baulks of wood to raise the block gradually to the level of the mastaba.

Once the block was on the mastaba, the siba came back into use to support the block so the wood could be removed and the block gradually tipped into position. This took all morning.

By noon the block was in its final position it’s shallowest end supported by a block of sandstone. Hassan, Mahmoud and the crew are justly proud of the work!

We have also built a second mastaba to hold the several inscribed and decorated ceiling blocks from Chapel D, like this one, that cannot be put back in place as not enough is left of the chapel (visible in the background). This will not only protect them from water infiltration but will also improve the appearance of the approach to the chapel and the Taharqa Gate.

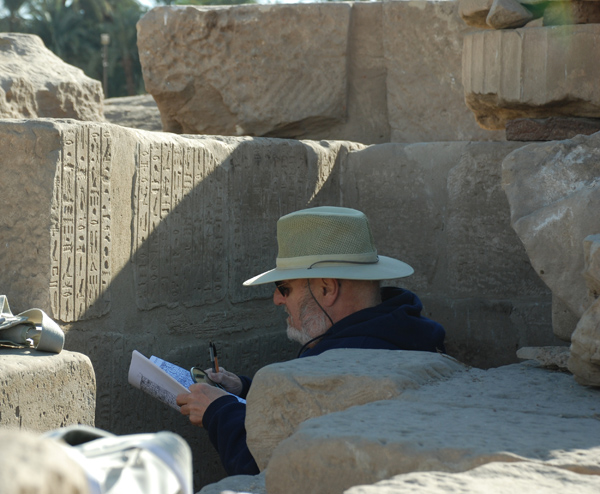

In the meantime, I have found time to start work in the Montuemhat Crypt, comparing Charles Edwin Wilbour’s corrections to Mariette’s copy of the texts with what is still on the walls. A small mirror is essential to direct light on shadowed areas of the wall. From what I have seen so far, many of Wilbour’s corrections are accurate.

Adding graffiti to temples is an ancient tradition that seems to be continuing today. The new paving in the gateway of the Mut Temple’s 1st pylon is only a few months old and already it has acquired its first graffito. The figure has a cobra on its forehead and what looks like a crudely carved beak (Horus?). It wears an elaborate crown with sun disk and a very fancy robe with checkered shoulder straps and diagonal lines on the sleeves. Pity the artist wasn’t more talented.

Jaap took this terrific photograph of two small lizards locked in combat.

And Julia contributed this photograph of a crow diving after a kite. Life is never dull at Mut!

Richard Fazzini joined the museum as Assistant Curator of Egyptian Art in 1969 and served as the Chairman of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art from 1983 until his retirement in June 2006. He is now Curator Emeritus of Egyptian Art, but continues to direct the Brooklyn Museum’s archaeological expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak, a project he initiated in 1976. Richard was responsible for numerous gallery installations and special exhibitions during his 37 years at the museum. An Egyptologist specialized in art history and religious iconography, he has also developed an abiding interest in the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. Well-published, he has lectured widely in the U.S. and abroad, and served as President of the American Research Center in Egypt, America’s foremost professional organization for Egyptologists.