The Work Begins

We started work at the site on January 5, but the celebration of Coptic Christmas (January 7) and Islamic New Year (January 10) has meant that our first week was only 4 days instead of the usual 6. We haven’t yet begun excavation, but have had a productive few days nonetheless.

The reeds along the shore around the Mut Temple were cut down late last year as part of a joint USAID/American Research Center in Egypt project to study the sacred lakes in the Amun and Mut Precincts. For the first time in years, we can walk the shoreline around the temple — or we could if the space weren’t still covered in camel thorn as well as a few remaining reeds. Cutting and hauling this prickly growth was made even more difficult by the steep slope on which they were growing.

Amazingly, after only 4 days, our workmen had cleared the vegetation from the slopes around the Mut Temple, and from Temple A and the whole front of the precinct. That’s a lot of camel thorn and grass that had to be hauled away to a spot where the dried weeds won’t present a fire hazard. Loading a truck with camel thorn is almost as much fun as cutting it in the first place. Since it’s almost noon, the man on the truck bed grabs a snack while waiting for the next batch of weeds.

This is view to the southeast of the rear part of Temple A, now clear of vegetation. Despite how it may look in photos, the precinct is not in an isolated spot in the desert. The main road to the airport runs just to our south, and apartment buildings are growing to the east as can be seen in the background here.

Jacobus (Jaap) van Dijk, of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, joined us on the 8th. Now that the vegetation is gone, he and I could spend part of that day examining the outer walls of Temple A looking for ancient graffiti.

We found this double graffito of a standing figure of the goddess Ma’at (the feather on her head identifies her) and a kneeling figure with arms raised in adoration. Such pious graffiti are not unusual on the exterior walls of temples. Some are quite elaborate and include inscriptions praising the god or goddess or recording the name of the person who carved the graffito.

The real work this week took place in Chapel D, the small Ptolemaic chapel just inside the Taharqa Gateway in the west area of the precinct. Restoring what is left of the chapel is one of our main conservation goals this season. The west wall of the middle room is of particular concern, as you’ll see.

While stone masons define the front edge of the middle room’s foundations, two other workers gently brush the loose earth from between the blocks of the west wall.

Before the wall could be taken apart, each piece of stone had to be numbered and the numbers keyed to a photograph. Otherwise reassembling the many pieces and putting them back in their original places would be very difficult. By the way, the numbers are not written directly on the stone but on an applied material that can be removed easily once the work is done.

We all thought the chapel’s west wall was made up either of two rows of stone or of one row of solid bocks that had split vertically. Much to our surprise, we discovered that the wall actually consists of two thin rows of blocks forming the exterior and interior surfaces of the room with a filling of small blocks and rubble between them. In the photo on the left (taken from above), the exterior facing is at the bottom of the photo and the decorated interior facing is at the top. In the photo on the right, the upper course of the decorated wall has been removed and the composition of the wall’s core is more clearly visible.

This shoddy construction method and the thinness of the decorated blocks may explain their poor condition.

As an aside, Chapel D is not the only structure on the site constructed of pieces of this and that. Temple A’s 2nd Pylon, built in the 25th dynasty and shown here, is also a hodgepodge. The south wing (top of picture) is made up almost entirely of re-used blocks, most taken from the site’s temple of Ramesses III that seems to have been out of use by then.

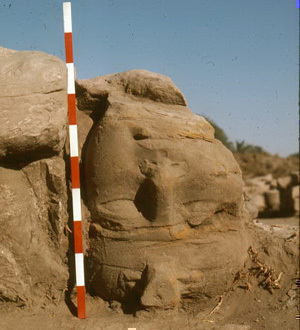

The north wing of the pylon has a mud brick core faced with sandstone blocks. Most are pieces of colossal statues, such as this upside-down torso and head, that have been cut apart and their rear surfaces smoothed to form the pylon face.

Now, back to Chapel D.

On the left, our conservator, Khaled, stabilizes a deteriorated block before it is removed from the wall. On the right, our mason, Mohamed Gharib and his son and assistant, Tarek, work on blocks that have already been removed.

The wildlife in the precinct can be beautiful, such as this flock of egrets taking flight from the shores of the isheru. However, some of it can be dangerous, such as the season’s first scorpion, photographed by Jaap before it was killed.

Richard Fazzini joined the museum as Assistant Curator of Egyptian Art in 1969 and served as the Chairman of Egyptian, Classical and Ancient Middle Eastern Art from 1983 until his retirement in June 2006. He is now Curator Emeritus of Egyptian Art, but continues to direct the Brooklyn Museum’s archaeological expedition to the Precinct of the Goddess Mut at South Karnak, a project he initiated in 1976. Richard was responsible for numerous gallery installations and special exhibitions during his 37 years at the museum. An Egyptologist specialized in art history and religious iconography, he has also developed an abiding interest in the West’s ongoing fascination with ancient Egypt, called Egyptomania. Well-published, he has lectured widely in the U.S. and abroad, and served as President of the American Research Center in Egypt, America’s foremost professional organization for Egyptologists.