A Coney Island Renaissance?

As many of the postings on Flickr illustrate, images of Coney Island frequently capture a gritty and often sadly neglected landscape. But this kind of urban exploration, especially of an area like Coney, which has always attracted a broad range of people and activities, has often been a stimulating and fruitful source of inspiration for photographers. The wide range of amusement and decay is brilliantly put on display in schveckle’s and Cormac Phelan’s postings on Flickr. These powerful images show Coney Island pretty much as it looks today, neglected but still colorful.

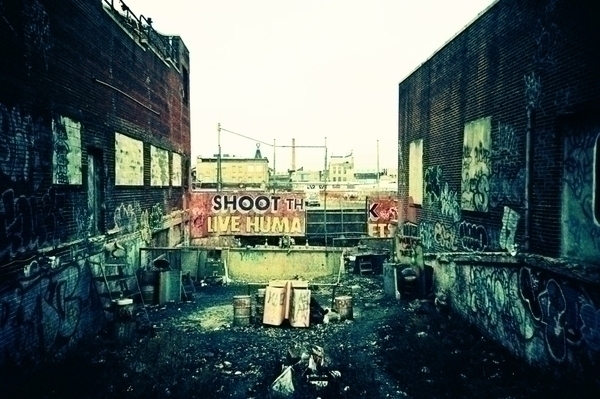

Shoot The Live Human, Cormac Phelan (from the Goodbye Coney Island? group on Flickr)

The straight-forward composition of Cormac Phelan’s gap between two buildings focuses on the sad remains of a popular game. Of course there is an element of humor, but there is also a disturbing atmosphere of gloom and even sorrow, both in the site’s state of decay and in the references to the game itself: Shoot the Freak. Live Human Targets.

hose play, schveckle (from the Goodbye Coney Island? group on Flickr)

schveckle’s creatively and composed snapshot is most probably taken right next to the gap in the previous picture, but here gloom is replaced by summer joy. The wonderful colors, the laughing biker crossing the boardwalk, the girl having a shower, and the onlookers leaning against the railing; nobody seems to be shooting the freak.

Steeplechase Pier, Coney Island, 1938. Sidney Kerner, American, born 1920. Gelatin silver print. Gift of the artist. 1995.128.1

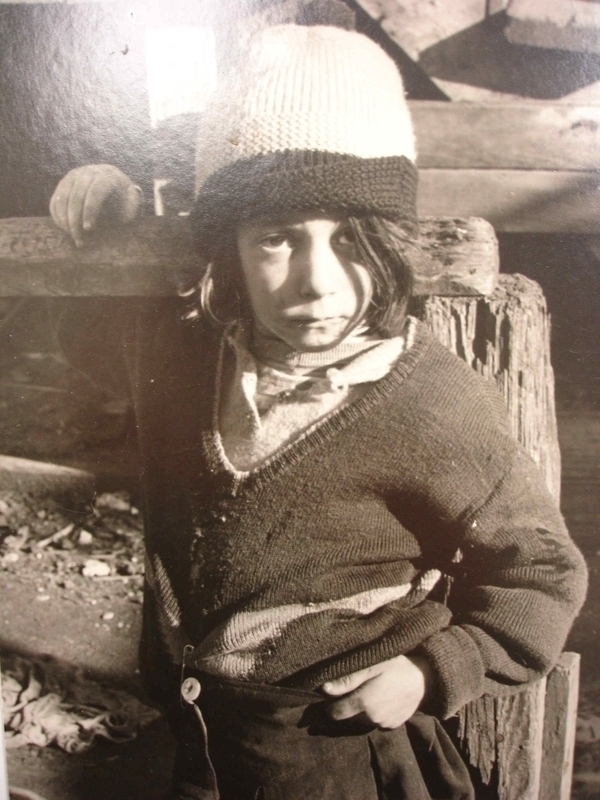

The depression years in the 1930s were difficult everywhere and this was the first time Coney Island really suffered a downturn, as a reduced disposable income made people less prone to spend money on entertainment. Enjoying the free beach and boardwalk promenades, the crowds still arrived in great numbers, but income from amusement concessions plunged even though many barkers and operators cut prices in half. Luna Park, one of the three original amusement parks, went into bankruptcy in 1933, and when it reopened after a brief closing, the park could only afford to light a fraction of its many bulbs. Many people, even families, used the space beneath the boardwalk as temporary shelter. In an effort to use the camera as a tool to reflect a difficult social climate, Sidney Kerner, a Brooklyn-born photographer, had joined Paul Strand’s and Berenice Abbott’s newly established Photo League in 1937, a year before he took his remarkable picture of a depression era kid on Coney Island.

Coney Island, Depression Girl with Safety Pin, 1938. Sidney Kerner, American, born 1920. Gelatin silver print. Gift of the artist. 1995.128.6

Air View of Coney Island Beach and Boardwalk, Brooklyn, 1946. Ben Ross. Gelatin silver print. Gift of the artist. 1998.34

In the prosperity that followed World War II in America, families found themselves with more money to spend, and Coney experienced a brief moment of renewal, with record crowds in the summer seasons of the late 1940s. But the rise of Coney Island in the postwar years was temporary, and from the 1950s, Coney was in steady decline. Postwar suburbanization, car culture, and the creation of parkways and public state parks such as Jones Beach offered people alternatives for day trips in the summer. Robert Moses, New York City’s powerful Parks Commissioner, objected to the kind of entertainment Coney offered with its penny arcades, shooting galleries, rides, and sideshows.

Out to sea, Marc Arsenault – Wow Cool (from the Goodbye Coney Island? group on Flickr)

In 1938 his Parks Department took control of the beach at Coney Island, with efforts to reduce the level of amusements. In the 1950s and 1960s large areas were used for new housing projects built on Moses’s initiative. Widespread gang violence in the 1950s frightened some visitors, and when Steeplechase closed for good in 1964 – a victim of rising crime, neighborhood decline, and competing entertainment – the area dedicated to amusement was dramatically reduced. At this time, a new amusement park, Astroland, had already been established for a few years between Surf Avenue and the boardwalk west of West Tenth Street. This park carried on the Coney tradition during the following decades.

Left: Coney Island, 1969. Stephen Salmieri. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Edward Klein. 82.201.4

Right: Burger Man, urbanshoregirl (from the Goodbye Coney Island? group on Flickr)

In the postwar period Coney Island remained an almost obligatory subject for most photographers visiting or living in New York. New and more affordable lightweight cameras allowed photographers to be freer in the exploration of their topic. Brooklyn-born Stephen Salmieri had just graduated from School of Visual Arts when he started his Coney Island series in 1966. Working in the tradition of many mid-20th-century independent photographers (such as Robert Frank and Lisette Model) who found Coney Island an inspiring subject, Salmieri spent the following six years in documenting a decaying area, still full of life. Coney Island as a democratic destination for everyone subsisted, as testified in Salmieri’s images as well as in many of the pictures on Flickr.

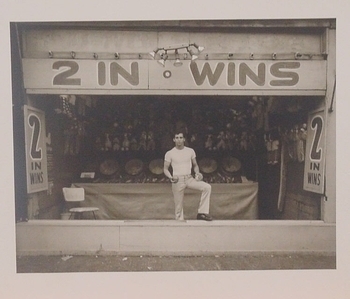

Left: Coney Island, 1969. Stephen Salmieri. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Edward Klein. 82.201.39

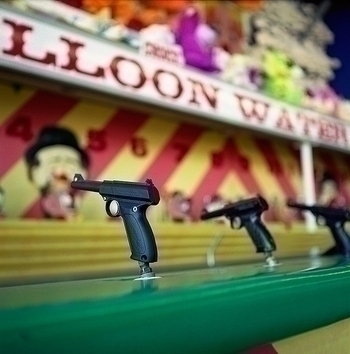

Right: ballon water, Supercapacity (from the Goodbye Coney Island? group on Flickr)

It’s wonderful to be able to juxtapose Salmieri’s photos with these contemporary images, showing that there is still a stretch of concession stands on the Bowery, not much different from the ones in Salmieri’s suite of images from forty years ago. Even though some barkers are now relying on electronic amplification to lure passersby to their games, the original intention remains the same. Look especially at supercapacity’s absolutely stunning rendering of a shooting gallery, an image where the spectacular composition and the play with focus communicate both humor and gravity.

Patrick Amsellem is the Associate Curator of Photography at the Brooklyn Museum. Formerly a curator at the Rooseum Center for Contemporary Art in Malmö, Sweden, Patrick organized the first Swedish exhibition of the work of Andreas Gursky and was part of the curatorial team that produced a major series of exhibitions under the leadership of Lars Nittve. He has written about art for Stockholm’s major newspaper Svenska Dagbladet and was also a critic for the Swedish daily newspaper Kvällposten and for Swedish Public Radio. Patrick has taught at New York University and is the author of several exhibition catalogues. He received a Ph.D. in Art History from New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts.