Who Was Demetrios and How Old Was He When He Died?

The mummy of Demetrios raises a large number of questions that can only be answered with the help of a team of scholars. Each of the team members brings a particular kind of knowledge to answer these questions. Their specialties include medicine, culture, language, and materials. I want to try to tie together some of the contributions made by all of the team members here.

I chose the mummy of Demetrios to include in the exhibition “To Live Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum” from Brooklyn’s nine human mummies. Demetrios was one of two mummies never unwrapped in modern times, a prime consideration for presenting him to the public in a respectful way. His wrappings were also in better condition than the wrappings of the other candidate, a woman named Thothirdes who is on view in the galleries in Brooklyn. So Demetrios’ mummy could travel more safely than Thothirdes. But Demetrios posed certain problems for me in explaining to visitors who he was.

Demetrios most likely died in the first century of this era (called both A.D. and C.E.) Carbon-14 testing suggests he died in the year 39. He was an Egyptian, but perhaps he had a Greek ethnic background. He lived in the time when Greek was the language of government in Egypt, following Alexander the Great’s conquest about 300 years earlier. He probably was born during the time of Cleopatra the Great and thus witnessed the change of Egypt from an independent Hellenistic kingdom to the property of the Roman Emperor.

Demetrios’ mummy was prepared in the manner called a “red shroud portrait mummy.” This means that over his mummy bandages priests wrapped a linen shroud painted red. In addition he had a portrait in the Greek style placed over his face rather than an Egyptian-style mummy mask. Also, the inscription on the shroud was in Greek rather than Egyptian hieroglyphs as was typical for most of Egyptian history.

The CT scan performed by Dr. Larry Boxt’s team at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, New York in 2007 revealed some of Demetrios’ medical history. Dr. David Minenberg recognized the gall stone preserved in Demetrios’ gall bladder, a feature of the scan I initially thought was a scarab! Dr. Boxt was the first to suggest that Demetrios had to have died in his 50’s rather than living to the age of 89 as scholars had first suggested in 1911 based on a reading of the inscription. Dr. Boxt based his estimate on the condition of Demetrios’ spine.

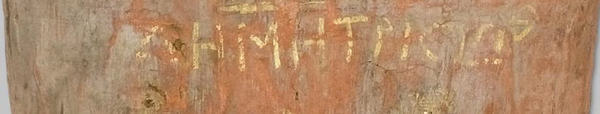

ΔΗΜΗΤΡΙС LΝΘ

Dr. Boxt’s observation led me to ask Dr. Paul O’Rourke, an expert in both the ancient Egyptian and the ancient Greek languages, to look again at the inscription on Demetrios’ shroud. He explained that the inscription recorded Demetrios’ name followed by a sign that resembles the letter “L.” The “L”-like sign indicated that the following letters should be read as numbers. In this case the first sign intended to represent a number was partially erased. The inscription showed two parallel lines that look like this: ІІ. Originally scholars interpreted these lines as the letter Π meaning “8” with the top missing. The following letter, Θ is complete and slightly raised from the line and means “9.” Together, scholars read his age as 89. But, Dr. O’Rourke pointed out, if the two parallel lines were understood to be the remains of Ν with the diagonal line missing, it would be the Greek writing of “5.” Thus Demetrios’ age could correctly be understood as 59, bringing it into line with Dr. Boxt’s observations of the spine. Knowledge of the aging of the spine helped determine how to restore the Greek inscription properly!

If you want to see Demetrios’ spine and his other bones for yourself, look at:

These web pages were prepared by Ed Bachta at the Indianapolis Museum of Art as part of the “To Live Forever” website. You can see Demetrios himself in Indianapolis beginning Saturday, July 12, 2008. Check with the Indianapolis Museum of Art for the details.

Edward Bleiberg is Curator of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Middle Eastern Art at the Brooklyn Museum. He joined the museum in 1998 after 13 years teaching Egyptian hieroglyphs and directing the Institute of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at the University of Memphis. A native of Pittsburgh, he graduated from Mt. Lebanon High School and Haverford College. After graduate work at Yale University and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, he earned an MA and Ph.D. in Egyptology at the University of Toronto. He is the author of books and articles on the ancient Egyptian economy, Egyptian coffins, and the Jewish minority in ancient Egypt and ancient Rome. Dr. Bleiberg has curated Jewish Life in Ancient Egypt, Tree of Paradise: Jewish Mosaics from the Roman Empire, and Pharaohs, Queens and Goddesses in Brooklyn. He is currently preparing To Live Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum a traveling exhibition on Egyptian burial customs opening in June, 2008. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.