Wilbour and the Stela of the Seven Years’ Famine: Part I

Wilbour’s letters to his family, kept in the Museum Archives, give a vivid picture of his travels in Egypt and the research he carried out there. Much of this work consisted of his checking earlier publications of Egyptian monuments against the originals themselves, but sometimes he was the first to discover and translate an inscription. In this post we can follow Wilbour making an important discovery on the island of Sehel in the First Nile Cataract, just south of modern Aswan.

At the First Cataract the course of the Nile is shallow and full of granite boulders: boats had to be towed through the rapids by the local fishermen (who charged a hefty fee), or a channel had to be dredged for safe passage.

Egypt – Fishermen at the first cataract, Philae. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection (S03_06_01_018 image 2369).

The boulders, however, were the ideal spot for kings to commemorate their achievements. They were the billboards of their day – but inscriptions carved into granite last longer than paper posters, and Wilbour was in his element discovering and copying these inscriptions. One he discovered, however, gave him particular problems:

Elephantine, February 6, 1889

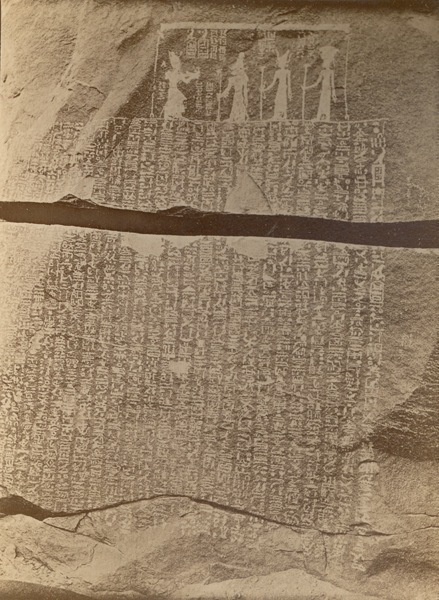

We sailed in half an hour up to the picturesque island of Sehel. … Thutmose III on a bigger piece of granite says that on the twenty-second day of the ninth month of his fiftieth year [c. 1425 BC], having ordered the cutting of this channel after he had found it boxed up by stones so that no vessels could pass, he rejoicing, sailed up to hew his enemies. The channel’s name was ‘Goodway Usertesen’; now its name became ‘the way made good by Thutmose III the immortal’, and, he adds, the fishers of Elephantine are to dig it out every year. But for many years these fishers have taken good care not to dig it out; they get money for pulling vessels up the way in which the stones seem to have been accumulating ever since Thutmose’s time. The best inscription I found was of thirty-two long lines, and very hard to make out, of a King Kharser, whose name I have never before seen. We rowed back in three-quarters of an hour.

Stela of ‘Kharser’. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Charles E. Wilbour Archival Collection [9.4.004]

Wilbour returned to Sehel the following year, with his family (‘Lottie’ his wife Charlotte, who was advised to stay in Egypt for her health; ‘Linnie’ and ‘Dora’ his daughters Eveline and Theodora; ‘Ned’ Eveline’s husband) and another Egyptologist, Professor Archibald Sayce of Oxford University, who had his own houseboat, the Timsaah (‘Crocodile’). He continued to work on his stela.

P 552 February 9, 1890

… Dr. Worthington and Sayce breakfasted with us; the doctor examined Lottie and reassured us that her lungs were unaffected. … Then came the mail with letters from New Bedford and Compton and Paris and elsewhere and papers from Montana telling of the election of Republican Senators. May they get in.

February 10, 1890

Went to Sehel and recompared part of the stele I discovered last year.. …

February 11, 1890

To Seheyl again in the morning. After noon we went to the west bank, Linnie and Dora to the old Convent and Sayce and I to Pig Rock, where we copied a store of inscriptions and a considerable fragment of a stele. Dora found the top of another. … In the evening Ned and I went to the Timsaah and Mr. A. P. Maudslay, who has worked seven seasons on the Mayan antiquities in Central America, showed and explained to us many fine photographs taken by him at Copan. He with four others of his family are on one of Cook’s new dahabeeyehs [houseboats], the Osiris.

February 13, 1890

…The unknown king of my stele bothers Sayce and me greatly. The character of the inscription puts it in Ptolemaic or Roman time and how a King not a Ptolemy or an Emperor could have reached the eighteenth year of his reign, passeth understanding.

February 16, 1890

…The Osiris came up and Maudslay gave Ned for me negatives, very fine, of my great stela at Sehel.

(adapted from Travels in Egypt: Letters of Charles Edwin Wilbour (Brooklyn, 1936)

The text of Wilbour’s stela told of a seven year famine in Egypt: the country was starving, temples were shut, law and order had collapsed. In a dream the Pharaoh saw Khnum, the ram-headed god of Aswan, who assured him that the Nile would rise again and the famine would end. In thanks, the King promised Khnum’s priests a share of the revenues from the land around Aswan.

For nineteenth century Egyptologists brought up reading the Bible, the Famine Stela was astonishing: it seemed to confirm the tale of Joseph interpreting Pharaoh’s dream of seven year’s famine.

Next week, I’ll post the second part of this story, where we’ll see what Wilbour made of this intriguing text and how he tried to make his Egyptological colleagues aware of his discovery. In the meantime, catch up on our ongoing series of posts about Wilbour, if you’ve missed any.

Tom Hardwick studied Egyptology at Oxford University, where he is working on a doctorate in Egyptian sculpture. He worked as Keeper of Egyptology at Bolton Museum in the UK, 2005-2009, and is currently volunteering in the Wilbour Library of Egyptology. He has published articles on Egyptian art, the history of Egyptology, and the history of collecting.