Wilbour and the Stela of the Seven Years’ Famine: Part II

The first part of this story showed the American Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour discovering and translating a long rock-cut text on the island of Sehel. Wilbour was very excited by the text. It described a seven year long famine in Egypt which was only brought to the end by the intervention of the God Khnum, the god of nearby Elephantine.

So who was the king named in the text and shown offering to Khnum and his divine family at the top of the stela? Wilbour tried to decipher the indistinct hieroglyphic signs of his name with little success.

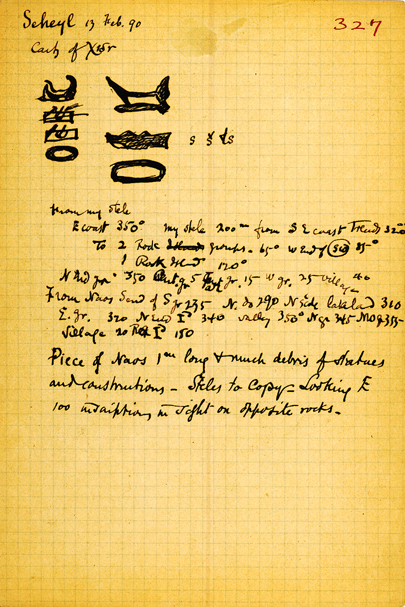

Wilbour’s notes on the royal name on the stela. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Charles E. Wilbour Archival Collection [5.1.019, notebook 3C, p. 327]

Wilbour could tell from the grammar of the inscription that it was written in the Ptolemaic Period (c. 300 BC), but how could a king have reigned for 18 years at this time without leaving behind any other traces?

We now know that the king named in the stela is Djoser, a king of the Old Kingdom ( c. 2800 BC): however, as Wilbour correctly recognised, the stela was written 2500 years later. It was probably created as a ‘pious fraud’ by the priests of Khnum, trying to boost their tax revenues and make their temple look older and more important than it was. The theme of the seven year’s famine may actually have entered the Egyptian text from a Biblical source, rather than the other way round: there was a thriving Jewish community at Aswan in the years before the stela was erected, and Wilbour himself would acquire some documents from this community in 1893.

An unusual coincidence in this story is Wilbour’s meeting with Alfred Maudslay, the British archaeologist who was carrying out groundbreaking excavations of Maya sites. In Central America Maudslay had to take and develop photographs deep in the jungle, away from a reliable source of water (a set of his photographs is now in Brooklyn), so photographing the stela for Wilbour would have posed little challenge.

Alfred Maudslay at Chichen Itza, 1889. Brooklyn Museum Library.

The small Western community in Egypt kept an eye out for interesting new arrivals, and Wilbour will probably have had advance knowledge of Maudslay’s arrival at Aswan. It is tempting to wonder what the two men discussed: the differences and similarities between Egyptian and Mayan pyramids? Did Wilbour, a keen linguist, give Maudslay tips on how to decipher the Maya hieroglyphs (something that was not achieved until the 1960s)?

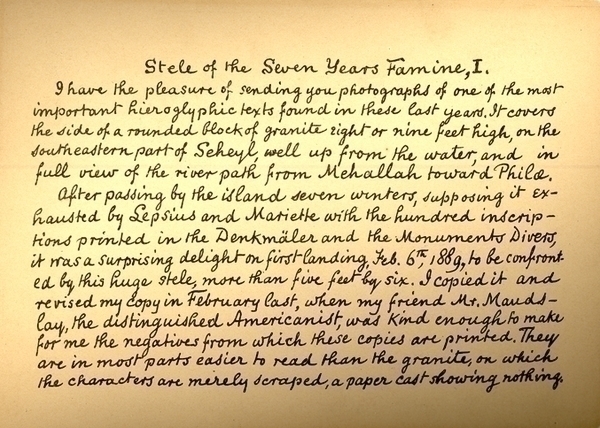

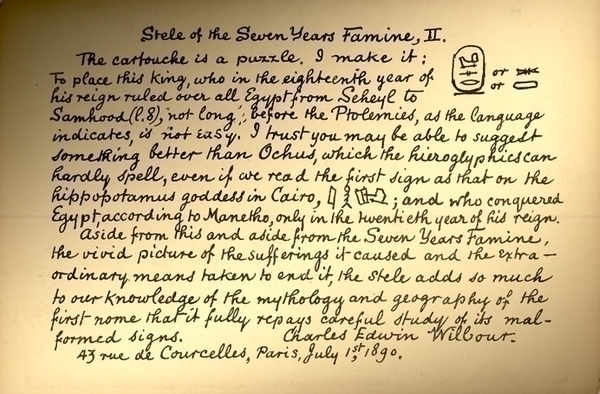

In April Wilbour left Egypt to spend the summer in France. He was still proud of his discovery of the stela, if puzzled by its text. Within a couple of months he had printed some cabinet cards of Maudslay’s photographs: the backs contained his own thoughts on the stela.

Wilbour’s description and analysis of the stela. Brooklyn Museum Archives, Charles E. Wilbour Archival Collection [9.4.004 and 005]

He sent these out to colleagues to arouse interest in this important text. His hopes were realised: within a year the stela had been fully published by the German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch. The famine stela has remained ever since a vital part of the study of Late Egyptian literature and religion.

Wilbour’s role in this episode is key—he discovered the famine stela, translated it, and disseminated it—but he was typically modest in the way he allowed Brugsch to be the first to publish an account of it. Did Wilbour, who never graduated from university, feel that he lacked the intellectual gravitas to do it? Given his background in the murky politics of Tammany Hall, did he feel he should keep a low profile? Perhaps he was just content to have solved the problem to his own satisfaction and felt no need to publish it.

One thing I particularly like about this story is the way it shows Wilbour using the latest technology of the age—cabinet cards—to reproduce the stela accurately and disseminate it as quickly and efficiently as possible. If he were alive today, would Wilbour would have been blogging about his discoveries to his friends?

Tom Hardwick studied Egyptology at Oxford University, where he is working on a doctorate in Egyptian sculpture. He worked as Keeper of Egyptology at Bolton Museum in the UK, 2005-2009, and is currently volunteering in the Wilbour Library of Egyptology. He has published articles on Egyptian art, the history of Egyptology, and the history of collecting.