What Do We Want from the ASK Wiki?

In one of my previous posts, way back in March 2015, I discussed our initial plans for a shared research database (an “ASK wiki”) which would be authored and referenced by our team to answer visitor question via the ASK app. Now that the ASK app has been live for almost 8 months, it’s time for an update!

The wiki has proven to be an essential part of the ASK project. It’s not only the team’s most thorough reference source, it’s also an important learning tool—after all, the best way to really wrap your mind around something is to write about it! The wiki is also a living resource, one that has grown dramatically, adapted to the needs of the team, and presented us with some unexpected challenges. And as a shared digital resource on the Museum’s collection, it still holds a lot of untapped potential.

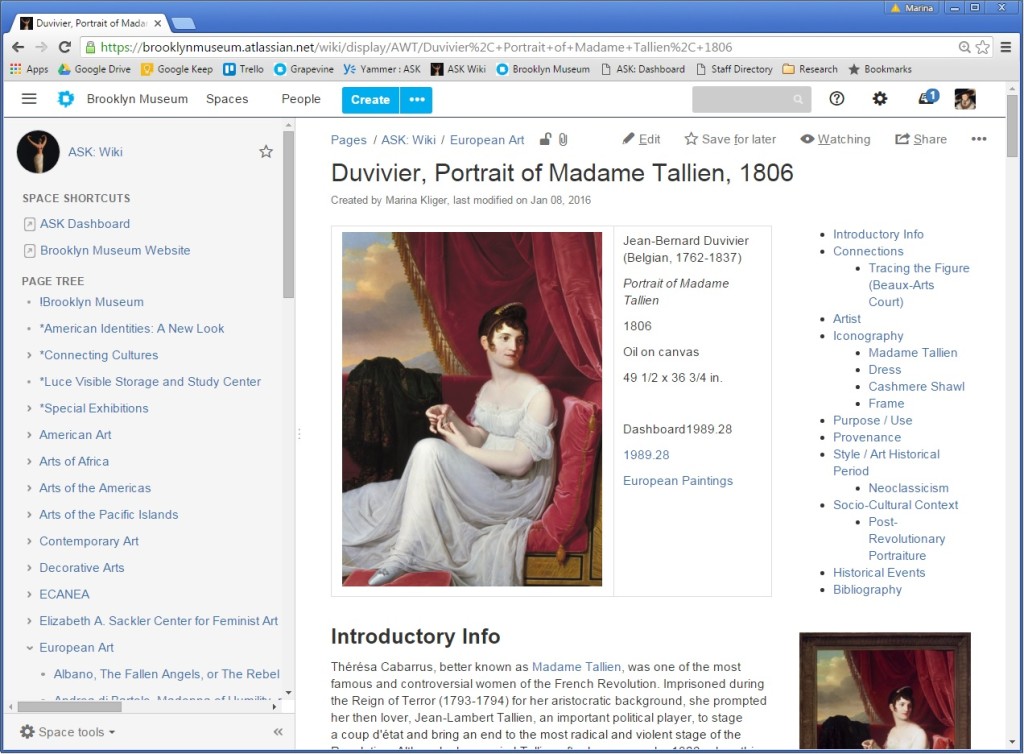

An example of an object page in the ASK Wiki. Information is organized according to discrete categories including Artist, Iconography, Purpose, Provenance, Style/Period, Socio-Cultural Context, and Historic Events.

First, let me say that we’ve made a lot of progress! Last spring, to get the ASK wiki off the ground, we selected and started writing about 10 objects from each of the 8 collection areas on view (about 80 wikis). As of today, the ASK wiki has expanded to 45 American Art, 26 African Art, 23 Arts of the Americas, 28 Contemporary Art, 50 Decorative Arts, 17 Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art, 46 European Art, 3 Arts of the Pacific Islands, 4 Asian and Islamic Art, and 1 Library wikis (243 total). Though this is only a fraction of the collection on view, the team starts new wikis every week so our database will only continue to grow over time.

All in all, the organizational principles we developed for the wiki last spring have worked well for the team. Rather than a narrative, catalog-style entry, the information in each object wiki is divided into consistent sections, such as Materials, Style or Cultural/Historical Context. This helps the team know where to go for answers to specific kinds of questions. However, user experience brings insight: As we’ve discovered how exactly the team uses the ASK wiki, we’ve adapted it to better align with their needs. For instance, we have reorganized the sections to highlight the kinds of information visitors tend to ask about most, like artist biographies and iconography. Often, visitors don’t even start a conversation with a specific question but rather with a photo or an expression of interest. (The first automated message they receive via the app is, after all, “Find a work of art that intrigues you. Send us a photo.”) To facilitate our ability to quickly respond to such open-ended inquiries about objects, possibly ones unfamiliar to the team member staffing the dashboard at that time, we’ve created a new section at the top of each object wiki with 3 sentences of essential information plus 3 interesting facts that might spark a good conversation. As we make more and more wikis, we have also noticed that some objects are very similar to each other and that creating new wikis for each one would be needlessly repetitive. (These works are sometimes displayed together in the same case, like 2015.65.1 and 2015.65.15, but sometimes not, like 41.848 and 40.386.) So we’ve implemented group object wikis that address a certain type of artwork, like ancient Iranian animal-shaped vessels or Egyptian Fayum portraits. Conversely, not all objects in the Museum’s collection have the same informational needs. It might be essential to know about the author of a European or American painting, but the maker of an Egyptian artifact is usually not known. So we have also created dedicated wiki templates for different collections, with sections that make sense for them.

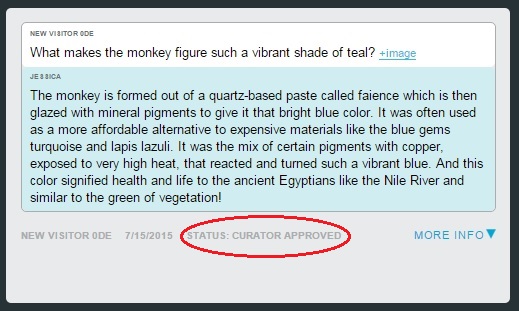

A “curator approved” snippet in the dashboard. This kind of snippet rises to the top of the heap when the team is answering visitor questions via ASK.

There are also some challenges that have proven more tricky to overcome. In our initial plan for the wiki, we envisioned that curators would regularly review and contribute to it in order to ensure the accuracy of its information. We knew, however, that the team’s priorities (breadth and basic data) would be different from curator’s expectations (depth and clarity of style) when reading about works in their collection. A team member might quickly create a wiki by copying and pasting information from one or two sources and come back to add more information over a period of several weeks—or they might not, depending on their availability and needs. So, in order to protect curators’ time and put our best foot forward, we devised a system for flagging wikis for curatorial attention only when I, as the Curator Liaison, had edited it for readability and updated it for comprehensiveness. This very quickly proved to be unfeasable. The 6 team members generated wikis at such as pace that it was too much for one part-time employee to edit and update consistently in order to maintain a stream of “finished” wikis for curatorial review. In other words, we had a MAJOR bottleneck problem. Moreover, without specific prompting, most curators or curatorial assistants did not have the incentive or time to contribute to wikis. Curatorial review of the wiki has, therefore, been minimal, even as the team continues to use it to answer questions.

However, now that curators are actively and regularly providing feedback on “snippets” (segments of past ASK conversations tagged to specific object IDs and provided to curators as a report), we are faced with two questions: 1) Is curatorial review of the ASK wiki, an internal non-public facing resource, as crucial as it seemed a year ago when we did not have a protocol in place for curatorial review of the team’s actual conversations with visitors; and 2) Is curatorial review of the ASK wiki now needlessly repetitive since any corrections the curators make to snippets are not only used to update them in the dashboard, but are also incorporated into the ASK wiki. These questions will only be answered through continued conversations with curators about their desired level of involvement and oversight. The solution to the bottleneck problem, however, might entail changing our own process of writing, sharing, and vetting wikis.

As a content-heavy, object-based digital resource on the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, the ASK wiki has a lot of potential for application outside the strict confines of the ASK app. For example, we’ve had a lot of interest from Museum Education, who like the ASK team are on the frontlines of interpreting the Museum’s collection for the public. Yet some of the ASK wiki’s benefits—its malleability, integrated content, and multiple authorship—make expanding it to the larger Brooklyn Museum community very very tricky. On the one hand, the more people who would potentially use and author object wikis, the more collection information would be available to all Brooklyn Museum staff, including the ASK team. In other words, object information siloed in individual departments could potentially get integrated into (or possibly uploaded to) a searchable digital resource available to all. On the other hand, the more cooks in the kitchen, the greater the potential for conflicting priorities, unruly entries, and quality disparities. That is, the information system we created for the ASK team works really well for the ASK team, but other users will inevitably have different needs. Expanding this easily writable and editable resource will, therefore, require more editorial, organizational, and curatorial oversight—which is exactly the shortfall we already face with our current 6 authors. It is absolutely a project worth pursuing, but it is also one that invites careful consideration by all parties, something we will be doing in the coming months.

Marina Kliger is the former Curatorial Liaison for the Bloomberg Connects initiative. She worked closely with curatorial and other departments to create and vet the knowledge base which the audience engagement team will use to answer visitor questions through the ASK app. She is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Fine Arts, where she is writing a dissertation about troubadour painting in early nineteenth-century France, and holds an MA in Art History from the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Before returning to graduate school in New York, she worked as a research associate at the Art Institute of Chicago—though she first came to museum work through a background in gallery teaching.

Start the conversation